Because I’m a middle-aged white guy, I was listening to a podcast recently. Even though it had nothing to do with coaching or even with sports, the host gave some advice I think sports coaches should heed.

…you cannot tell people what they should care about, right?

You can’t say, ‘this is so important, I implore you to care about it.’

You can’t give me caring homework. It doesn’t work that way.

- Adam Conover

I remember early in my coaching career, I would talk about how frustrated I felt it was to “want it” more than the players I worked with “wanted it”. I felt I was so much more competitive than they were. Since I thought they didn’t care enough, I thought one of my jobs was to get them to care about our sport and about winning as much as I did. I needed the meme-ified Narrator to set me straight.

Getting players to care about what you care about as much as you care is challenging, complex work. So don’t do it. Stop assigning caring homework. Stop making it their job to want what you want the way you want. It’s not that you shouldn’t take on challenging work, it’s deciding which challenging work you ought to be doing. Beating your head against a wall is challenging work, but there are ways to break down walls that involve better tools.

There are two terms that appear often in psychology literature that come to mind when talking about “wanting it” and caring. The first of these is passion. To quote Robert Vallerand and colleagues, “Passion is defined as a strong inclination toward an activity that people like, that they find important, and in which they invest time and energy” (p. 757)1. For Vallerand, there’s also an element of identity that goes along with passion: “passions become central features of one’s identity and serve to define the person” (p. 757). You likely feel passionate about the sport you coach and about competing. You likely feel that such passion is necessary for success. That may be true, but that’s not the point. Passion isn’t something that is forced on someone, it is something that is felt and nurtured.

Players in your care may like the sport they’re playing and they may spend time and energy playing it but that doesn’t mean they find it important and are strongly inclined to play it. And that’s okay. They may even be highly skilled at the sport and not feel passionate about it. That’s okay too. As much as you’d like for the players to feel as passionate as you do, demanding that they feel that way isn’t how the research on passion says you should do it. (This doesn’t mean that you have to lower your standards or your expectations, but that’s a post for another day.) The challenge, instead of demanding passion, is seeking out interest and nurturing it when and where you find it.

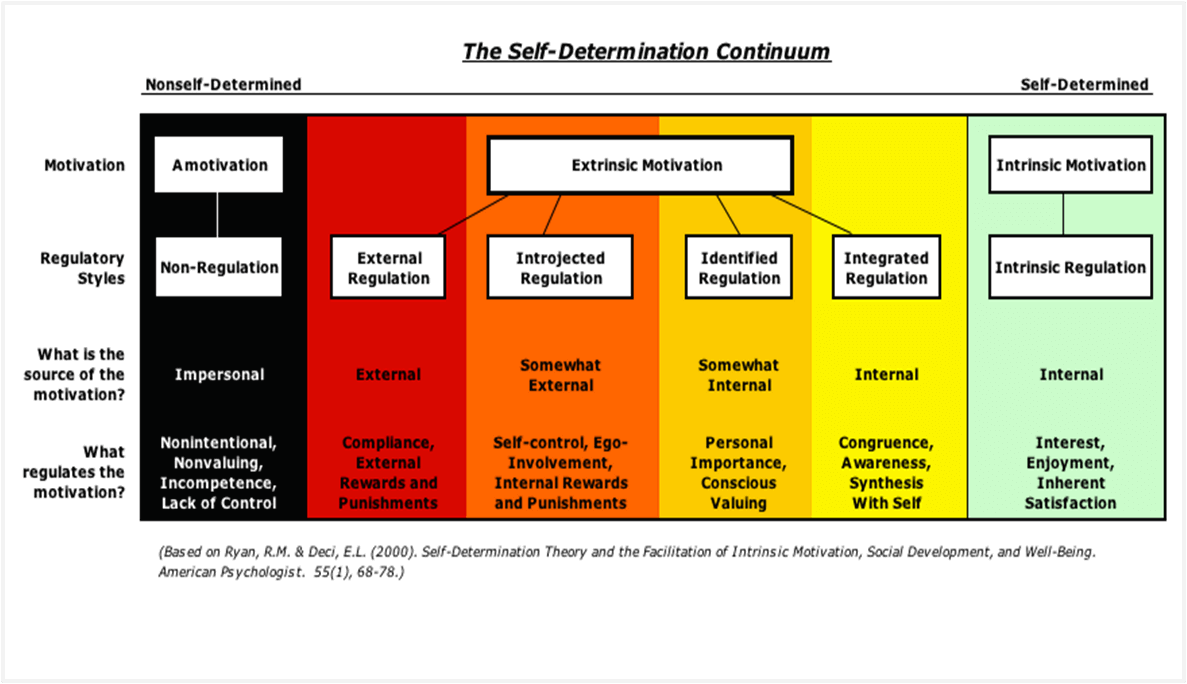

That brings up the second important term, motivation. Motivation is a very complex psychological construct and I’m not going to come close to fully describing it here, but I will give you a little bit of information and insight. Many scholars have developed the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation but I’m discussing these two kinds of motivation from the perspective of Deci and Ryan’s Self Determination Theory. To give you an idea of how complex these terms can be, here’s a visual representation of Deci and Ryan’s model of the continuum on which intrinsic and extrinsic motivation sit.

What’s important for this discussion is that extrinsic motivation is often seen as controlling, as opposed to autonomous. Coaches often rely on extrinsic motivation, the clichés of carrots and sticks, to get players to do what they believe must be done to achieve success. But, because most extrinsic motivation is a result of controlling behaviors, it rarely nurtures passion. Like passion, intrinsic motivation should be nurtured and supported rather than expected and demanded. (Again, this doesn’t mean that coaches can’t hold high standards and expectations, but you shouldn’t expect those to tools to create intrinsic motivation by themselves.)

If there’s any kind of caring homework being assigned, it’s being assigned to you. Your homework is to work with athletes to figure out what they find important and worth doing. They may have little practice at exploring such questions because we adults have always told them what to do and because they haven’t been doing anything long enough to become deeply acquainted with it. But they can’t get good at exploring those questions unless they’re exposed to them. I don’t advise trying to get players to want exactly what you want, but I do think you can find common ground with them if you seek that common ground instead of demanding that players adopt your values without compromise.

Passion and intrinsic motivation can be nurtured through shared vision. Michael Gervais described Pete Carroll’s notion of shared vision as one in which both people nod and want to work together on it. Inviting players into conversation about what they care about in the sport, in practice, and in competition creates opportunities for coaches to align what they care about with what the athletes care about. What each person cares about doesn’t have to align perfectly with what the other cares about, the coach is just seeking places to make connections. That’s what nurturing intrinsic motivation and passion can look like. If you want passion to come out of them, you have to help them find it within themselves first.

Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., Léonard, M., Gagné, M., & Marsolais, J. (2003). Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85 (4), 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756