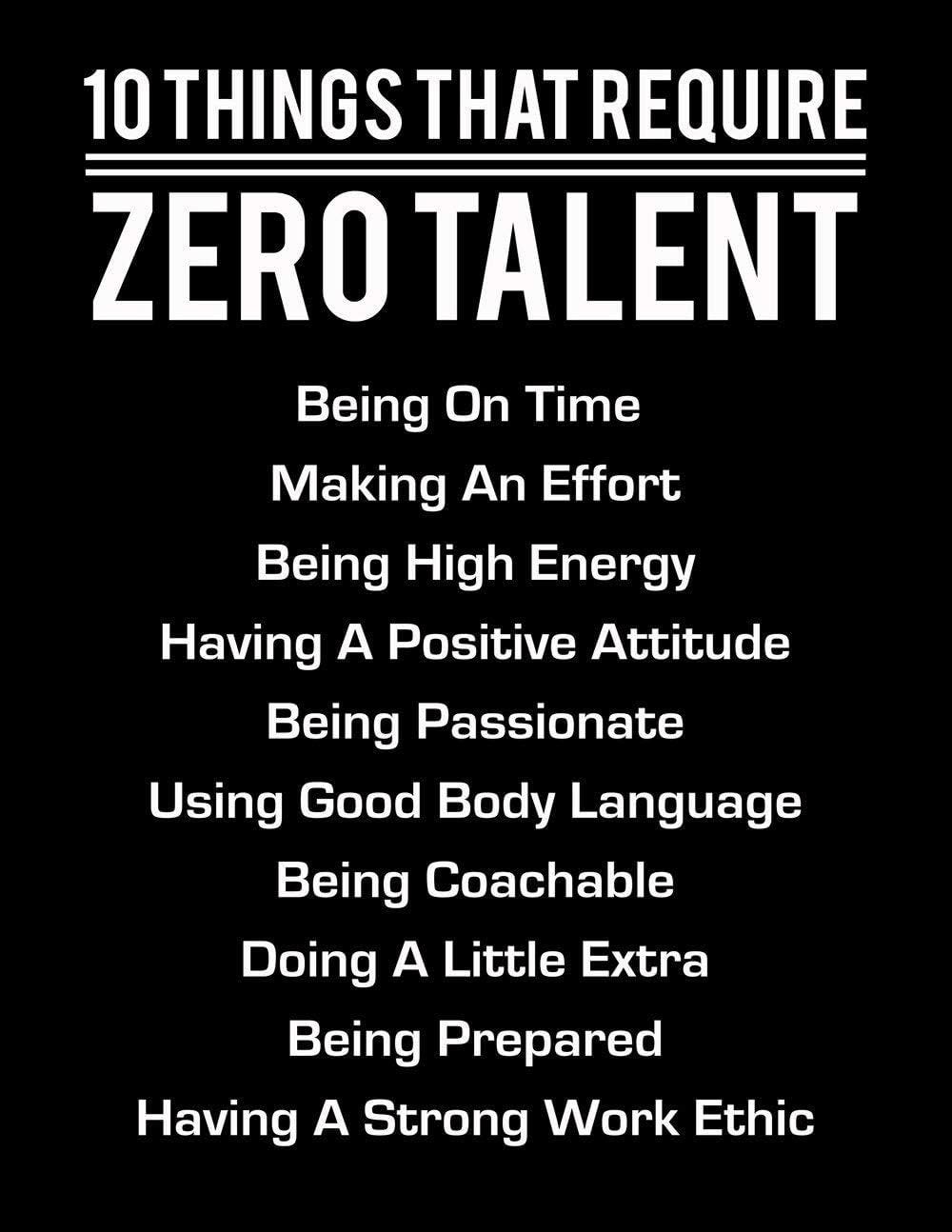

You know that list of things that “require zero talent”? If you aren’t familiar with it, first, that’s not a bad thing, and second, here it is…

There isn’t anything wrong with any of the traits on the list, each of them is admirable in their own right. My issues with the list arise from the inference that, because the items don’t require any talent, everyone should do them and that doing them will make up for any lack of talent. But, even deeper, I don’t agree with the unspoken premises about talent.

What is talent, anyway? If you work from the context given by the list, it seems talent is something innate, something in you that gives you an almost unfair advantage over others in competition with you. When it comes to sports, it would seem that most talents are related to physical traits. An example would be the old cliché, “you can’t teach tall.” But talent is generally assumed to be more than just the body you got through a roll of the genetic dice. I’ll quote from one of my favorite academic papers, The Mundanity of Excellence by Daniel Chambliss1, to explain how “talent” is often viewed.

Some have “it,” and some don't. Some are “natural athletes,” and some aren’t…When children perform well, they are said to “have” talent…We believe it is that talent, conceived as a substance behind the surface reality of performance, which finally distinguishes the best among our athletes. (p. 78)

Chambliss is saying that what you call talent is mostly just a made-up word to explain the amazing performances you see because you can’t wrap your head around how amazing things can come from normal processes. He goes on to say that such a broad concept of talent fails on at least three points: that factors other than talent better explain athletic success, that talent is basically just another term for outstanding performance rather than an explanation of that performance, and that the “amount” of talent needed for success is actually quite small. He doesn’t deny that physical differences matter, but he highlights that those differences are far from the best way to explain differences in results. But, he says, allowing talent to explain differences in results allows you to say that some people are just better than others and there’s nothing to be done about it because no one knows how those talented people are able to do what they do.

So talent is this convenient thing that allows you to create a way for some people to be better than without facing some tougher truths. Chambliss, again:

In the mystified notion of talent, the unanalyzed pseudo-explanation of outstanding performance, we codify our own deep psychological resistance to the simple reality of the world, to the overwhelming mundanity of excellence. (p. 81)

Again, he’s saying that, if you really looked at it, you’d be flabbergasted by how normal it was to go from zero to hero. I think that’s what the list is supposed to address, the “simple reality of the world”, that, beyond physical differences, there isn’t nearly as much separating you from people with “talent”. You aren’t born with passion or coachability. But, if you are passionate and coachable every day, you can catch up to the talented people. I can’t agree with that.

I can’t agree with that because none of the traits on the list actually make you better at the things you’re competing at. Being prepared and having a great work ethic by themselves don’t make you run faster or jump higher. Doing the things on the list put you in the best possible position to get the most out of the actual work you still have to do, which is how you become excellent (or talented) at something. But don’t mistake preparedness and work ethic for the actual work. Your energy and effort are catalysts for the work, they are things that, when added to the work, make the work more efficient and more beneficial.

Chambliss writes:

When a swimmer learns a proper flip turn in the freestyle races, she will swim the race a bit faster; then a streamlined push off from the wall, with the arms squeezed together over the head, and a little faster; then how to place the hands in the water so no air is cupped in them; then how to lift them over the water; then how to lift weights to properly build strength, and how to eat the right foods, and to wear the best suits for racing, and on and on. Each of those tasks seems small in itself, but each allows the athlete to swim a bit faster. (p. 81)

You can see how being passionate and having a positive attitude can contribute to learning those skills a little better or a little faster but “learning a flip turn” isn’t on the list of things that require zero talent. But that doesn’t mean a flip turn is a talent. It isn’t a talent, it’s a skill.

People will acquire different skills at different rates and the people who acquire them the fastest will be thought of as “naturals”. But they still had to figure out how to perform the skills, even if that learning seemed effortless. That’s what Chambliss was driving at, talent, as it’s typically thought of, isn’t very real but skills are. Jumping high isn’t a talent so much as it is a skill. You figure out how to jump and then you do it more and get better at it. If others (and even you) don’t realize all the work that goes into your “talent”, that blind spot doesn’t magically make the skill something that you could always do. Skills are real and so is the work that goes into them.

That’s another thing about the list, you’re supposed to believe that everything on it is a talent, but a talent that everyone has. If everyone has them, they aren’t special. If they aren’t special, they aren’t really talents. I agree they aren’t talents but I believe they are still skills. I don’t like that people assume that you should just be on time, like it is a natural thing. Just like jumping higher, you have to get better at being on time by doing the work required. Being born with certain physical or mental traits means very little without work to apply those traits to skills that use them.

That list of things that require zero talent? It’s not a shortcut to achieving excellence. It’s not a substitute for the work. If anything, it’s a list of things that make the actual work of achieving excellence better. But, with the list or without it, with special traits or without them, there’s always work to do.

Chambliss, D. F. (1989). The Mundanity of Excellence: An Ethnographic Report on Stratification and Olympic Swimmers. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/202063