Proactively Thinking Like a Pro

The video above comes from a 2010 Allstate commercial featuring Guillermo Ochoa, then the goalkeeper for the Mexican Men’s National Soccer Team. I couldn’t care less what he’s selling because all I can see him promoting is how an athlete can mentally prepare themselves for performing skills. He’s thinking his way through how to defend against a penalty kick and the video gives viewers some idea of how he might be doing it. He imagines himself making several different moves to save several different kinds of shots he might face. In the end, he confidently responds to the shot that is taken and successfully saves it.

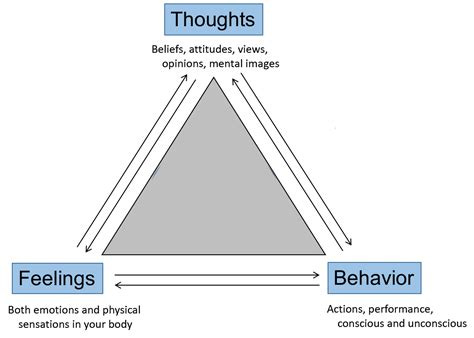

This video is a useful introduction to what Cognitive Behavioral Therapy refers to as the “cognitive triangle”. There are three parts to the cognitive triangle: thoughts, feelings, and behavior (more specifically, actions). These three parts, or phases, appear in both proactive and reactive cycles. I’ll refer to them as cycles since they tend to keep going in the same order in which they start. Ochoa models what I refer to as a proactive thought cycle. A proactive thought cycle sits in contrast with a reactive thought cycle, which can be found quite commonly in sport. What separates the cycles is the order in which the phases occur.

In general, “reactive” is defined as “acting in response to a situation rather than creating or controlling it.” In sport, you can argue that you can neither completely create nor completely control the situations you are in. This is a major reason why sport is so attractive, because you are continually confronted with new problems to solve rather than following a script to a known conclusion. You are constantly challenged to adapt in response to changing conditions, strategies, and opponents. Those who do it the best are the winners.

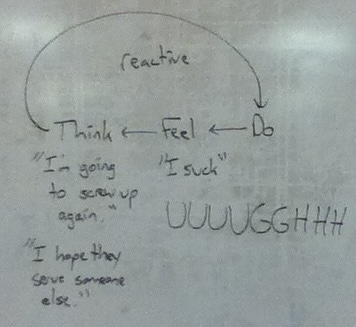

Reactive thought cycles go from actions to feelings to thoughts. First, you “do”, you go out and execute a skill. Then you “feel”, you have an emotional response to the skill you just performed. Last, you “think”, you have a mental response in which you analyze your action and your emotion. To understand what “do, feel, think” looks like, consider how you often see players function in practice.

Imagine a player performing a skill in practice. This is “doing”, or “behavior” as it appears in the triangle above. It is common to see the player, unhappy with their performance, immediately mimic the move they just made in order to correct themselves. This response demonstrates both aspects of “feel”, the emotion of unhappiness and the physical sensations of what they should have done. The athlete quickly moves on to thinking about what just happened and their thoughts frequently include judgments of themselves and their abilities.

Alternatively, I define proactive as “creating situations that move towards goals and anticipate future needs and changes.” But if sport is about constantly responding to dynamic situations, then how can you create situations? The answer lies in where you create the situations. In a reactive thought cycle, the situation is entirely external, players wait until after something happens to them before they address their internal state. Being proactive means creating an internal environment that will best prepare them for the ever-changing external environments that exist in sport.

A proactive thought cycle begins with “think” instead of “do”. Before executing a skill, a player thinks their way through the skill by telling themselves specifically what they’re going to do, just as Ochoa visualized. The “feeling” phase can use both senses of the word. The player can prompt positive feelings (emotions) like, “I can do this.” They can also incorporate a modeling of the skill they want to execute (physical), preparing their body for what is to come. This can be either internal (visualization), external (modeling), or both. Having prepared themselves for what may come, they execute. As best as they can, they “do”.

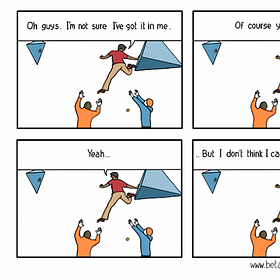

A reactive thought cycle tends to reinforce a fixed mindset because players see themselves in light of their outcomes rather than their processes. What they went through to arrive at the outcome is discounted, even if the outcome was out of their control (like a bad call from an official) and they wrap themselves up in the results. They are no longer in control of their internal environment because they allow it to be determined by their outcomes. They allow themselves to become a victim of their circumstances when they don't have to be.

A proactive thought cycle, on the other hand, encourages more productive thoughts, feelings, and actions. A player can more easily maintain control of the process in every phase and they can more easily keep themselves in a place where they are free to perform because they aren’t battling out-of-control judgment and emotion. But learning to control thought cycles takes work, often with the help of others, which brings us to how to coach the development of a proactive thought cycle.

First, plan to work on thought cycles as part of skill training. I don’t mean that there will be a section of your practice in which players just stand there thinking. Doing is part of the triangle and each part of the cycle affects the other two so it is crucial to keep all three phases interacting as they normally do. In a typical practice, the players practice physical skills and you give feedback on those skills. When you work on mental skills, the players still perform physical skills but your feedback (or, as you and they get the hang of it, your feedforward) brings attention only to players’ thoughts and feelings rather than to their actions. This means that you can set up a drill/game/activity as you normally would and things will run as they typically do.

In fact, an observer might not notice any difference in a practice that works on thought cycles. As athletes are practicing physical skills you are giving feedback about mental skills rather than physical ones. I’m not saying give feedback on both mental and physical skills, I’m saying give feedback only on the mental skills during the time you set aside for mental skills. Focusing your feedback in this way sends the message to the players that there is value in paying attention to the thought and feeling parts of the triangle. Your focus on these skills promotes the same focus in the players.

Maybe the most important aspect of helping players create a proactive thought habit is intervening before they perform a skill instead of after. Instead of critiquing their previous performance, set them up for success on their next one. The players are likely to be accustomed to reacting to their previous actions so breaking out of that thought cycle means bringing their attention to their next action without placing emphasis on their prior action. This is how you help them shift from a reactive thought cycle to a proactive one, by breaking their habit of relying on their actions to inform their feelings and thoughts. Because you’re changing the way they attend to their own performance, it’s important that you focus on their thoughts and feelings rather than on their actions. Paying attention to their actions would only reinforce the reactive thought cycles they already use. Not until both you and they become comfortable with thinking and communicating in a proactive way will it be time to go back to feedback on action. The goal is to plant and tend a rose where a thistle had been growing.

You want to help players plant thoughts about what they are about to do. My trusted way to work on thoughts during practice is to ask players what they want to pay attention to most in the upcoming activity. Because the focus is on thoughts rather than actions, there aren’t right or wrong things to focus on, as long as players are focusing on things in the future and not things in the past. In the future, when players are better at thinking proactively, there will be a productive way for them to tie their past actions to their future actions. But early on in this process, your job is to keep bringing their awareness to their thoughts. Do this by asking players how often they were able to keep their focus on the thing they said beforehand was most important. Ask them where their minds went when they did lose focus. Then, ask them again what they want to focus on and give them another opportunity to notice how their thoughts unfold.

As players grow more comfortable with leading with their thoughts, you can move on to helping them shape their feelings. As mentioned previously, there are two types of feelings to work with, physical feelings and emotions and, regardless of which one you’re working on, you’re working on priming the player’s brain and body to perform. To address physical feelings, connect back to what they want to focus on in the upcoming activity, as you did above. Follow up by asking them what they want the thing they’re focusing on to look and feel like. You want them to model the action they want to pay attention to. To address emotions, help players create an anchor. Talk to them about times they have felt strong, powerful, confident or successful. As they talk, notice their body language. How do they physically express those emotions? You’re looking for a simple movement or gesture, like a fist pump or a facial expression, that you can suggest as an anchor that will remind the player of those positive feelings. Once you have an anchor, you can remind the player of that anchor to help them establish positive thoughts and emotions prior to a rally or an activity. The goal for you is to teach players to string together deliberate thoughts and feelings before they start performing. Continue to ask them how often they were able to focus on the thing they said was important and where their mind went when they lost focus.

Asking players about their focus and their thoughts is part of mindfulness training, helping the player stay present and observing their internal state as well as their performance. Once they get used to creating thoughts and feelings before they perform, they can begin using those thoughts and feelings to compare and evaluate their actual performance. It’s important that the thoughts are comparative rather than judgmental. This means that they aren’t saying that their performances were right, wrong, good, or bad. Ask them to compare the performance in terms of similarities or differences. This gives them a bridge back to the beginning of the cycle because their comparisons can then inform their next execution (“bring my foot more forward next time”). You can also help them shape any changes they want to make by inviting them to speculate on what results the changes will create. If there’s a physical change that you want them to make, you can ask questions like, “what would happen if you got your left foot forward on the next one?”

All the questions above are shaped so that the players’ responses give you insight into where their minds are. Do their thoughts regularly wander? Suggest different things to focus on that may hold their focus better. Do their answers show that they’re thinking about actions to change or maintain? That shows that they’re in a proactive cycle of “think, feel, do”. Do their answers drift towards the judgmental or the emotional? That shows that they’re changing to a reactive thought cycle. You can intervene and get them back on track by asking them what they want to do on their next contact. Feedback like this helps the player re-establish a cycle in which thoughts instigate feelings and actions.

Teaching players a proactive thought cycle is similar to teaching any new skill. The process will slow practice down because it requires extra interaction between you and the players. You can minimize this effect somewhat if the activity you choose has multiple small groups of athletes performing skills. Other groups can practice normally while you work with one group at a time. As with any habit you nurture, it becomes easier and faster over time. The more you work on these skills, the more the work becomes a matter of maintenance so it becomes easier for practice to proceed normally.

Teaching new skills is challenging for both players and coaches. There is additional challenge when teaching a proactive thought cycle because players are often accustomed to being passive, mindless, and reactive. But if players are allowed to be passive, you will always be coaching backwards, looking at what just happened. Thinking proactively is better at looking forward instead of backwards. Teaching players to think proactively engages them more effectively. As players become proficient at thinking proactively, they become more confident and empowered. You help them see themselves as vital actors instead of helpless victims in the unfolding of the dynamic situations that they find themselves in.

The dry erase board images above are from a practice in which I introduced a team to proactive thinking cycles. The “feel” and “think” examples were supplied by the athletes when I prompted them during our discussion. Thanks to Tim Engels for introducing me to this concept many years ago.

Confidence is a Feeling

What is confidence? Is it coolly sinking the go-ahead basket as time expires? Is it calling your shot before hitting a home run? No. These actions might be expressions of an athlete’s confidence, but the truth is that confidence is the feeling that precedes those actions. And that feeling follows the thought of possibility.

Proactive Coaching: Discipline Now Sets Up Freedom Later

In Leading With the Heart Mike Kryzewski wrote, “Whatever a leader does now sets up what he does later. And there's always a later.” I believe that coaching proactively is the deliberate practice of continually setting up “laters” for athletes and teams.

Creating the Freedom to Compete

I hope that you were able to watch all the Olympics your eyeballs could handle. I’m still catching up on events that I didn’t get to see live. One event that I did see live was the men’s high jump final and I saw something in that competition that I wanted to share.