My favorite characteristic about Jason Watson is how genuine his vulnerability is. In talking with him, he regularly expresses his doubts and his drive to change and learn, but without coming across as lacking in self-esteem or intelligence. It’s a fine line and he walks it with ease. He is the head volleyball coach at the University of Arkansas.

What is “One Player at a Time”? - read here

When Jason first became a head coach, he won a lot. And yet, it didn’t feel right. When he reflects on his time in charge at BYU, he doesn’t think that he showed much empathy there, or at least not the way he does now. It wasn’t until he traded Provo for Tempe, taking over at Arizona State University, that he started changing the kind of coach he wanted to be. As he put it, “you get introspective when you’re not winning.” One of his assistant coaches talked with him about allowing players to get to know him better. But this wasn’t about having the team over to his house for social time, it was about communicating and sharing more in the unstructured moments.

While he does see some value in structured times, like team social gatherings, Jason talked about the psychological math players are often doing in those settings, “what’s the minimum amount of time I have to spend in this structured setting so my coach thinks I’m invested?” So connecting better couldn’t be expected in those settings. Even player meetings and video sessions weren’t going to be the right choices for “humanizing” the coaching experience. He wanted his work to be done in unstructured moments but still in the proper context. If Jason wanted to shift his coaching style and make genuine connections, he realized it needed to happen in the gym.

While Jason and I talked about the cliché “they don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care”, we both acknowledge that it means more than nurturing social connections. Jason understands that caring is much more than asking how a player’s day is going or how they did on their last math test. Caring is learning what brings a player into his program, honoring their motivations, and working together on a shared vision of the future. Jason is a great example of how that’s done.

Early in his time at ASU, Jason brought in a two-time Gatorade State Player of the Year. Cassie (not her real name) had set her high school team to back-to-back state championships but she was coming to ASU to be a libero. There were plenty of people, both in Cassie’s circle and in the public, that didn’t think changing positions was a good idea but Cassie and Jason shared a vision of her future, one in which she was a successful collegiate libero. Working towards this vision of the future was made even more challenging when ASU’s starting setter was sidelined with an injury part way through Cassie’s first season. This forced her into the setter position for a large portion of the season, which could have interfered with her progress as a libero.

The original plan for Cassie had been to have her redshirt her first year so she could just learn a new position and then be able to play four years after that learning period. The injury to ASU’s only setter could have derailed that plan completely. Jason and Cassie were each taking big risks by changing her position and the injury situation would have been an easy way to go back to what was safe and comfortable but they stayed committed. Jason says that practices went on with Cassie spending time passing and defending, just like they had planned. When it was time to compete in practice and matches, Cassie would set. Despite the obstacles, it was always clear that they would continue to work towards the same goal as before.

By continuing to honor their shared vision of the future despite obvious challenges, Jason was showing consistency. But, to him, there are important ways that he can be consistent in smaller moments every day as well. One of his best is “emotional consistency”. He talked about how easy it can be to “lose your mind if the effort isn’t right.” but he realized that kicking ball carts wasn’t going to make it any easier to maintain connections with players. Instead, he recognizes that players are more receptive to him when they don’t feel like they have to worry about invoking his wrath. This emotional consistency means that he doesn’t have to yell in the gym one day and then prove to players that he is considerate during individual meetings the next day. He has learned to be consistent in the unstructured moments. And by being consistent, emotionally or otherwise, in the small ways every day, he makes it easy to stay true to his word when the big moments (like Cassie having to set) happen.

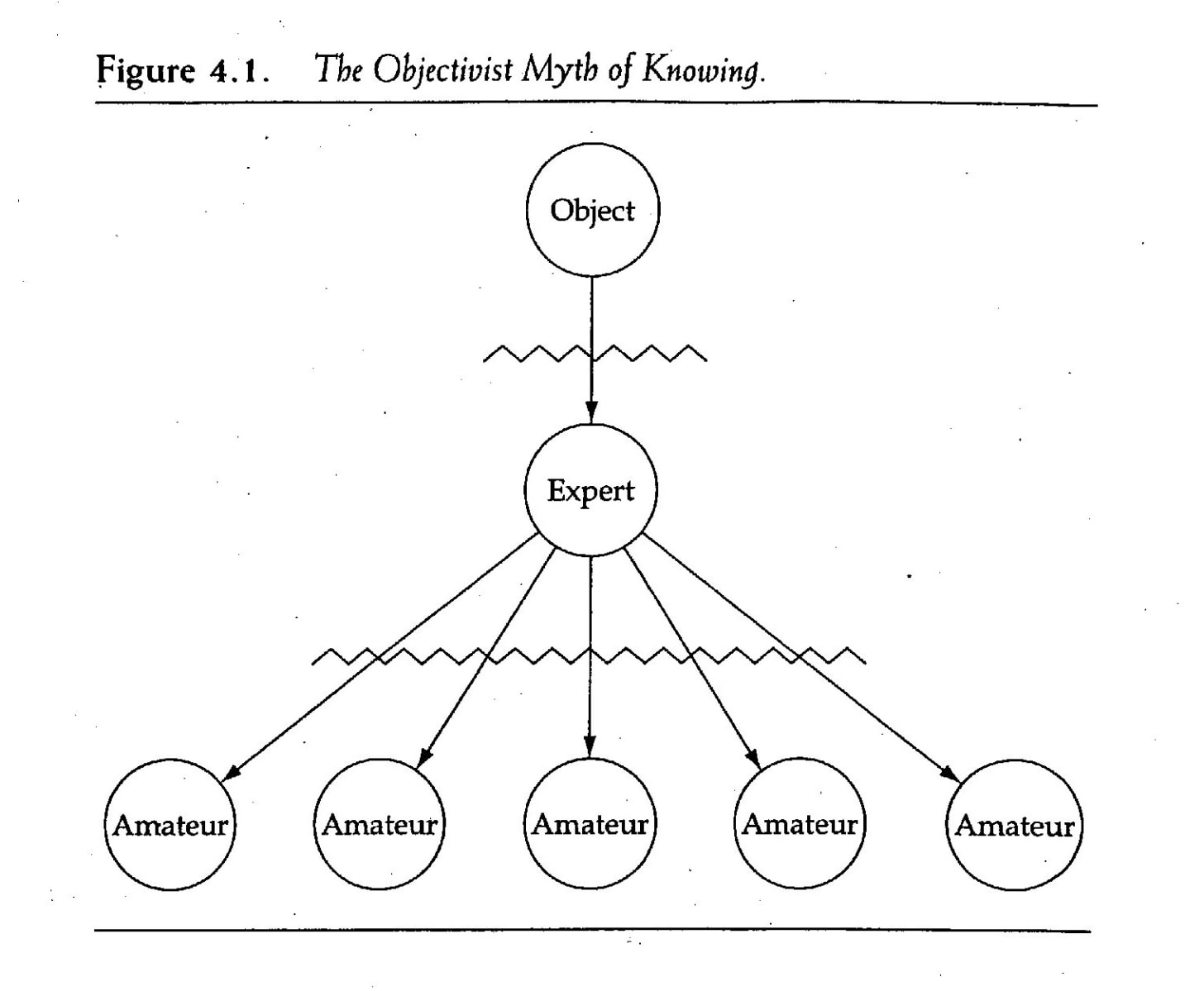

Jason spoke of how shifting his coaching allowed him to let go of some long-held images of what a coach should look like. He told me that he used to think that he should act as though he was the “sole source of knowledge” as a coach. I’ll illustrate this using a diagram from Parker Palmer’s book The Courage to Teach.1

In this model, coaches function as the expert, the person who must interpret the knowledge of an object for the amateurs in their care. When coaches do this, there’s only one way to learn anything, by acquiring knowledge from them. This can be an easy way to coach because there’s always a clear answer to players’ questions and needs. But Jason wanted to walk alongside the players instead. This shift had many implications for how he should conduct himself as a coach.

“Walking alongside” Cassie meant two things to Jason, helping her navigate a space that she had never been in and showing her that she would never be alone through that difficult journey. While part of navigating that space is the technical training, there are other important aspects. Jason highlighted this when he talked about how, prior to ASU, he likely would have relied heavily on the concept of “do your job” and expected that the technical training Cassie was receiving was all she needed to do her job. Since ASU, Jason says that he must also “define the job as clearly as I can for you.” He recognizes that he can’t assume that he and the players always understand things the same way unless he has made responsibilities and expectations explicit. Once he has done that, then he has another opportunity to be consistent, staying true to the descriptions they have discussed. One way Jason does this is by occasionally playing the role of “Chief Reminding Officer” for the team. He reserves the right to remind them of what they are trying to do or how hard they said they should be working. He’s just bringing them back to their agreed job descriptions.

An important consequence of Jason’s shift to walking alongside the players was that he had to acknowledge their many reasons for being in the gym. Previously, he might have assumed or expected that they either share or adapt to his reasons for them to play. Cassie wanted to be the best libero she could be, hopefully one of the best in their conference, even though she might not receive accolades because, at the time, ASU was near the bottom of the conference. Jason didn’t have to force her to accept a different standard, like being an All-American or even All-Conference. He could accept that what Cassie was aiming for was already a huge goal. In his words, “how brave do you have to be to make a change and not know what the outcome is going to be?” He is always asking players to be something that they are not yet and that is a big deal. He has to appreciate how large they perceive the gap is between what they currently are and what they are striving to be. He has to learn how strongly they believe they can close that gap between what they are and what they might yet become. Only then can he truly walk with them.

The best lesson that Jason learned from his experience with Cassie is a direct result of how he walked with her through her time at ASU. “Initial ability has no correlation to final ability,” he told me. Neither of them knew what the outcome would be at the beginning of their journey together. But she was brave enough to trade what she was for what she was not yet. She was brave enough to trust Jason and the other coaches. Jason honored her bravery by always supporting her and doing so consistently, despite the complications. As a result, she left ASU far better than she came in. ASU was a better program for her contribution. I dare say Jason became a better coach for all that he learned during that time too.

(Want to read more about the power of yet? Read here.)

Have questions for Jason? You can ask me here or you can email Jason directly.

Palmer, P. J. (2017). The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. John Wiley & Sons.