Number Theory - Setter Evaluation with Josh Steinbach (part 1)

Location, location, location is important but far from everything

Most of the time when I talk with other volleyball coaches and the topic of non-volleyball books comes up, the list of books gets pretty short. But not with Josh Steinbach. He might say it’s because of his degree in English Lit but I say it’s because he’s always looking for new sources of inspiration and learning. It’s fun to try to keep up with him. He readily admits what he doesn’t know and eagerly seeks to learn more about those topics. I think our conversation about setter evaluation is a perfect example of that.

What is Number Theory? - Read here

Josh Steinbach is adamantly “not a math guy”, though he has learned some math and statistics in his time coaching. He recounted a time when he thought one of his coaching decisions was based on some kind of statistics but, it turned out, he was really just coaching with his gut. One of his assistant coaches at the time actually had a degree in math and they told Josh, “what you’re doing doesn’t make sense.” After that, he figured he better improve that part of his coaching.

Though he has become more comfortable with stats over time, that knowledge has made him perhaps less comfortable with how impactful coaches can actually be during a match. In his estimation, “I’m good for one or two points in a match.” If that’s the case, then he wants to do whatever he can to make sure those points are meaningful and positively influence the outcome.

For Josh, one area of the game he feels he can have an impact on, both during competition and in training, is setting. He’s believed in the importance of setting to determining competitive outcomes for some time and the COVID-related shutdown in 2020 offered him an opportunity to work on quantifying setting. Going into the project he had an idea, a rating scale for setting he had seen that combined the outcomes of both the reception and the attack to rate the sets in between. (You can download a Word document version of the paper here.) He asked Joe Trinsey what he thought of the idea and Joe responded that it wasn’t statistically relevant (and I’m inclined to agree). That kind of put Josh back at square one but there was a kernel of an idea that Josh identified and still keeps in mind when thinking about the skill. Setting, Josh said, is “skill dependent on both sides”, meaning that what the setter can do is influenced by the contact prior (either a pass or a dig) and the setter is judged to some extent by what happens on the attack afterwards.

Josh and the assistants he worked with in 2020 studied setters from the top four teams in their conference, watching video of matches involving those four teams from the previous four seasons. They were driven by questions like “what do ‘advantage us’ and ‘advantage them’ mean?” They were in search of things they could quantify that setters did that created an advantage for their team or gave their opponents an edge instead. While they didn’t reach any kind of satisfactory point in their analysis, Josh said he at least figured out that allowing opposing setters to set with their hands was definitely an advantage. Even though the project was put aside, Josh said, “it gave me something to work on during practice, telling attackers not to groove balls to left back.” But he still didn’t have a tool he could use to evaluate setting.

In fairness to Josh, evaluating setting is a really hard problem. We did not solve the problem in the course of our discussion but the content of the discussion provides some great insight into how decision makers and information providers can work together to make progress on really hard problems.

When I asked Josh what he wanted to evaluate about setting, perhaps the most salient part of his answer was when he said, “if I have two setters and the team is running a 5-1, am I picking the right one?” He wanted to have data to inform and support his decision, rather than doing some version of coaching with his gut. For him, the coup de grâce would be one big equation that contained all the factors that affect setting, each weighted appropriately. Such an equation would, if he supplied all the inputs, give him a number that would quantify the setting skill of any setter. Think of something like Baseball Prospectus’ PECOTA or 538’s CARMELO metrics that seek to describe a player’s entire performance ability. It’s certainly a worthwhile goal but it’s complicated by all the intangible skills coaches would like to measure, not to mention that even the tangible skills of a setter are tricky to measure. I don’t make any claims that Josh and I discussed everything we’d like to measure about setter ability, but here are some of the areas that kept coming up during our conversation.

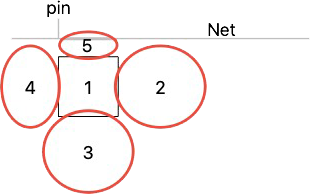

We discussed one aspect of setting that some people already measure, location. Both of us learned this idea from the aforementioned Joe Trinsey. I’ve used his model to evaluate set location for all the matches I’ve analyzed in my time at Colorado. In that model, there are five buckets you can classify set locations into. Looking at the diagram below, which represents the five locations for a set to a left side attacker, you can see how the areas break down. I have numbered the areas according to how frequently they occur in all the sets I have graded over the last eight years. Beyond that, the numbers have no meaning.

Area 1, the black box, is the location of a “good” set. Sets in this area allow the hitter to keep the rhythm and timing of their footwork and attack the ball at the peak of their jump while being able to hit in any direction they choose. (You may notice that there’s already aspects of location you can’t see in a two-dimensional diagram, height and tempo, but know that those are taken into account when a set is graded by watching it.) Area 2 is for low and/or inside sets. These are sets that prevent the attacker from hitting down the line because they either force the hitter to change their approach to the right or the ball may be traveling so fast through the attacker’s window, they can’t reasonably hit line. Area 3 is for sets off the net far enough that the hitter has to either shorten their approach or they are forced to jump straight up or even away from the net to attack. Area 4 is for sets outside the attacker relative to the center of the court. The antenna (or pin, as it’s labeled in the diagram) is the dividing line for this area because as soon as a set is parallel to the antenna, the hitter rapidly loses area they can attack in bounds. Area 5 is for sets that are tight to the net, preventing the attacker from hitting the ball hard without touching the net or going under the net. Each of these areas is associated with an expected attack efficiency, so a setter’s location can be assigned a number which represents how well an attacker should be expected to score, given how well the setter locates their sets.

But, Josh points out, just evaluating setting based on location doesn’t tell him everything he wants to know to about setters’ abilities. Part 2 will get into some of the other areas that matter to Josh in setting.

Have questions for Josh? You can ask me here or you can email him directly.