This series is an adaptation of my 2024 AVCA presentation of the same name. I have posted the video and slides previously. You can find links to the presentation video, slides, and resources at the bottom of this post.

This is part 4 of the series. In this part, I’ll show how magical coaching isn’t actually separate from classical and jazz coaching and what it takes to bring magic into your own coaching. You can find previous parts here:

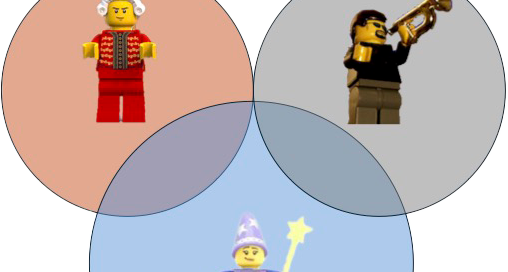

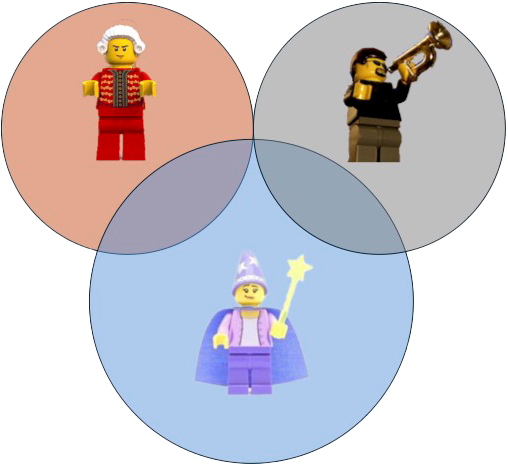

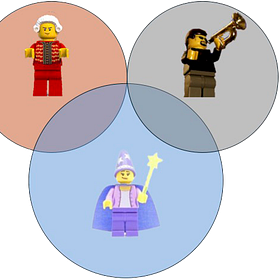

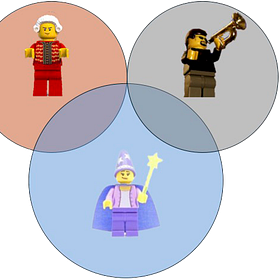

In part 3, I introduced magician coaches, described frames, and explained how frames impact problem setting. I ended by pointing out that, when problem setting, magician coaches bring themselves into both the problems they set and the solutions they seek. I also said that being a magician isn’t separate from being a classical or a jazz coach. The relationship looks a little more like this:

A magician isn’t using a different paradigm than the “Society as Machine” trick or the “Society as Organism” trick. A magician coach recognizes they are part of the machine or part of the organism and that fact impacts their problem setting in profound ways. Again, philosopher Donald Schön explains:

“We are…at once the subjects and the objects of action. We are in the problematic situation that we seek to describe and change, and when we act on it, we act on ourselves.” (Schön 1984, p. 347)

Schön is saying that magician coaches embrace the fact that they are part of the situations they seek to change and, further, embrace that they are changeable parts of those situations. That perspective radically changes the questions coaches ask themselves when problem setting. Here’s a table of examples of how magician coaches ask problem-setting questions:

Notice how the questions invite the coach to consider their values when setting problems. Questions like these make unstated premises more clear and allow the coach to work from a better-defined frame. Stating suppressed premises allows a coach to ask better questions of themselves and their own coaching but doing so also makes asking questions of other coaches much more productive. Instead of assuming that everyone is working from the same frame, a magician coach asks questions of others that include some information about their own frame and values so that listeners have more insight into what matters to the questioner. This gives the listener a cue to respond to the question by including their own frame and values. Look at the examples in the table below.

The first question comes from a classical coach’s perspective because it implies the existence of attitudes that are correct, or that fit into the coach’s image of how athletes should work. The question is built on an unstated premise that “good” attitudes exist, can be clearly defined, can be learned, and should be sought after. There’s nothing wrong with believing those things but, by suppressing the premise, a coach asking this question doesn’t help a listener understand what makes a good attitude. The conversation two coaches might have around this question is likely to leave both confused because they can’t be certain they’re talking about managing the same thing.

The second question comes from a jazz coach’s perspective because it seeks to understand the connections between athletes, their emotions, and their performance. The question is built on the unstated premise that those connections are important. Again, there’s nothing wrong with believing that but the suppressed premise will still inhibit the conversation two people might have around the question. If the listener thinks emotions don’t matter in competition then it’s difficult to answer the question in a way that is meaningful to the questioner.

The third question gives the listener some insight into how the questioner views the situation in question. Stating some premises (what a “bad” moment is and what my job is when one occurs), gives the listener a chance to respond with their views on what bad moments are as well as what their job is in those moments. This question gives the two people involved a better chance at having a meaningful conversation because they have more background information to work with that ensures that they are, at least to some extent, discussing the same thing.

I make the example of discussions between coaches because I think making such discussions better will improve your ability to learn from others through conversation. But learning how to bring out your unstated premises also improves your ability to learn on your own. You learn better by reflecting on what matters most to you and on who you want to be in a given situation. This is true whether you are learning on your own or learning from others.

In part 5, I’ll give a few more reasons why what you believe and who you want to be in a situation is so important to great coaching. I also briefly discussed these reasons in part of a post at the end of my series on developing a coaching philosophy. You can read that here:

Music and Magic (part 5)

This series is an adaptation of my 2024 AVCA presentation of the same name. I have posted the video and slides previously. You can find links to the presentation video, slides, and resources at the bottom of this post.

Music and Magic

Here are my video and my slides from “Music and Magic”. I edited out the discussion times but the content is all there. While I think there’s value in watching the video and looking at the slides, I think that the magic here is in the thoughts and the conversations you can share with others to facilitate your reflection.

Music and Magic : Resources

Here’s the page with the video and slides for the presentation itself. Below that are notes and references for the presentation.