This series is an adaptation of my 2024 AVCA presentation of the same name. I have posted the video and slides previously. You can find links to the presentation video, slides, and resources at the bottom of this post.

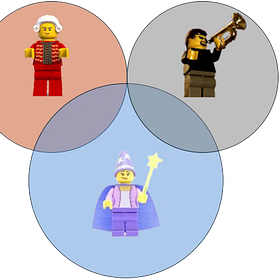

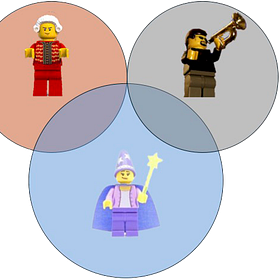

This is part 3 of the series. In this part, I’ll give more detail about how classical and jazz thinking influence your perspective on situations and I’ll give you a way of moving from good coaching to great coaching. You can find previous parts here:

In part 2, I described classical and jazz coaches, how they each view the world and learning, and how they set problems as a consequence of their views. To get a better understanding of how those different views impact problem setting, watch this clip of an interview with Herbie Hancock, a renowned jazz musician. In it, Hancock describes an interaction with Miles Davis in which Hancock saw their shared situation through a classical lens while Davis saw the same situation through a jazz lens. In particular, listen to how Hancock describes mistakes.

Hancock speaks of playing something “wrong” and of making “a big mistake”, and then he speaks of Davis doing something “right” and changing Hancock’s mistake into something “correct”. Hancock is exemplifying a classical lens and describing their playing as part of Becker’s “machine trick” of viewing the world. He describes the notes he played as though he was following a mutually-understood set of rules and he had strayed from that music in a way that just couldn’t work. He believed that view so strongly that he stopped playing and put his hands on his head. He believed that he had broken the machine. He had accidentally stepped outside of the “systematic procedure” Becker described as being part of keeping the machine humming along.

Maintaining the classical view, Hancock goes on to describe how Davis fixed the mistake Hancock had made. From that perspective, Davis found some notes he could play that, retrospectively, brought Hancock’s chord back into the machine so that everything could keep running smoothly. Hancock is inferring that Davis quickly asked himself the question, “what needs fixing?” and found a technical solution - a thing he could do to address the problem he had set.

Now, listen to Hancock reframe the experience from the perspective of a jazz coach. Note how he describes Davis’ view of the chord Hancock played and how Davis viewed his own responsibility.

Hancock shifts from words like “right” and “mistake”. Hancock instead speaks of “something that happened” and of finding “something that fit”. This language is more in line with Becker’s “organism trick” of viewing the world. Hancock had accidentally challenged Davis to find a new connection they had not worked on before. Jazz coaches expect variation within complexity and look for the effects such variation may have on the process. Davis wasn’t seeking a “right” way of playing, he was seeking a way that made sense and still kept things moving in the direction he envisioned, even if they got there by taking a new path.

What I find so amazing in these two clips is how Hancock is able to shift his perspective from classical to jazz. Either perspective can provide an adequate description of what happened and both views set a reasonable problem that can be solved. What I’m saying is that you can be good at coaching regardless of if you see yourself as more of a classical coach or more of a jazz coach. So don’t get hung up on classical versus jazz. Instead, get hung up on good versus great.

As I said in part 1, the fight I wanted to start wasn’t between “right” and “wrong”, which means the fight isn’t between classical and jazz coaching either, since they both offer a reasonable way of viewing things. To see what the fight actually is, I first need Donald Schön to explain value of reflection.

“When a practitioner becomes aware of their frames, they also become aware of the possibility of alternative ways of framing the reality of their practice. They take note of the values and norms to which they have given priority, and those they have given less importance, or left out of account altogether.” (Schön 1984, p. 310)

Schön is describing the value of what Hancock did in his interview, making himself aware of the frames people use to view the world. Hancock learned how to see situations through different frames and that’s what I’m inviting you to do, learn how to use different frames to make yourself a better coach. Recognizing and choosing frames allows you to set different problems for yourself and for the athletes in your care.

The fight I want to start is between the version of you that’s good and the version of you that’s great. The fight is between the version of you that reflects on the frames you use for problem setting and the version of you that doesn’t reflect on those frames.

The Magician Coach

The coaches that reflect on their problem-setting frames are magicians. To explain a magician’s frame, I’ll go back to Miles Davis. Here’s a clip of a song called “Blue in Green”, which is an example of modal jazz:

There's no obvious melody, chorus, or verses in this song. There is a structure (modes) but that structure is not apparent to an untrained ear. So how should you think of this structure? I’ll quote George Russell, considered a forefather of modal jazz, to explain:

“You're free to do anything, as long as you know where home is.”

“Home” is the frame you see your world through. For Miles Davis, part of “home” was, as Herbie Hancock described, not hearing things as “mistakes”. To do anything magical, you have to know the frames you use.

Magician coaches see “home” as who they are and what they want to be in relationship to their environment. They are rooted in values and beliefs that transcend the objective standards and/or subjective connections that classical and jazz coaches see. Their values and beliefs create a framework that allows them to judge how well their decisions are working out. They’re interested in how a given technique/tactic fits into their philosophy or in what kind of situation would have to arise in order for that tactic to work for them. “Home” helps them decide what makes the most sense to them in a sea of possibilities.

To a magician coach, knowledge is not a thing to get and pass on but a relationship. “Knowing” something means knowing their relationship to it. Magicians recognize their values and beliefs are parts of the situations they are in. The problem is it’s hard to share knowledge of “home” because “home” is about you and your relationship with situations you’re in. Your relationship with a situation will be different than mine and that can be challenging to articulate. (Remember the “house” example in part 1?)

Here’s a table that summarizes the kinds of questions a magician coach applies to situations. (Compare this to the same information I offered in part 2 for classical and jazz coaches.)

Notice that, unlike the questions classical and jazz coaches ask, these questions bring the coach into the problem and into the solution. That’s an important distinction that I’ll explain more in part 4. Until then, if you’re wondering how to develop your personal “home”, go back and read my series, “Developing a Coaching Philosophy”:

In part 4, I’ll show how magical coaching isn’t actually separate from classical and jazz coaching and what it takes to bring magic into your own coaching.

Music and Magic (part 4)

This series is an adaptation of my 2024 AVCA presentation of the same name. I have posted the video and slides previously. You can find links to the presentation video, slides, and resources at the bottom of this post.

Music and Magic

Here are my video and my slides from “Music and Magic”. I edited out the discussion times but the content is all there. While I think there’s value in watching the video and looking at the slides, I think that the magic here is in the thoughts and the conversations you can share with others to facilitate your reflection.

Music and Magic : Resources

Here’s the page with the video and slides for the presentation itself. Below that are notes and references for the presentation.