It’s Not Complicated

It’s Just Overdetermined. And Probabilistic.

Your mind is playing tricks on you. All the time. I’m not talking about hallucinations or optical illusions. In the last ten years or so, a lot of attention has been brought to the kinds of tricks your brain is pulling on you. The tricks I’m talking about are called logical fallacies, heuristics, and biases. You can read about them in books like You Are Not So Smart and Thinking, Fast and Slow. There are two tricks that I want to highlight because of how they work together to limit your coaching.

The first trick is often called the fallacy of the single cause or causal reductionism. Here’s a great summary of the trick:

Outcomes in sports are often overdetermined, meaning they had multiple factors that contributed to the observed outcomes. But it’s hard for you to keep track of those factors, so your brain reduces the many factors to a single, salient cause. Here’s a non-sports example of overdetermination, the cost of eggs.

The headline and lede of this story say it all, in Colorado there are several factors that are contributing to higher costs but most people see only one cause, bird flu. If you look at causal reductionism in coaching, it looks something like this.

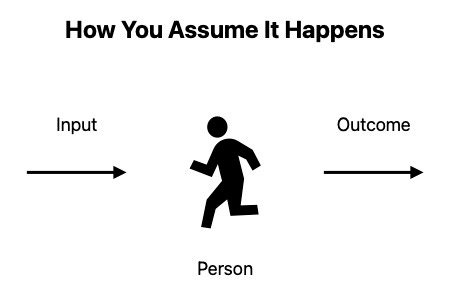

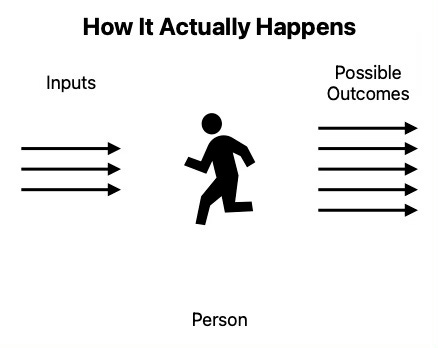

A player you are coaching does something, your brain picks out one thing that it decides caused what you saw, and you structure your feedback to the player as though their decision, their action, and the outcome were all determined by that one thing you noticed. The truth of the situation is there were different inputs that all influenced the outcome without any single one of those inputs completely determining that outcome by itself. A better way of describing this situation would be to change the diagram.

You can’t get rid of causal reductionism. So how would you coach players differently when you acknowledge that causal reductionism happens to you? You would ask more questions of yourself and of the players. In your usual way of coaching, you would almost immediately decide what the cause of an event was and start giving feedback about that cause. But fighting the human habit of causal reductionism means that you’re not looking for a single cause any more. When you keep your mind open to multiple causes, before giving any feedback, you would ask yourself what other causes contributed to the event you witnessed. You would do it not to see if your original diagnosis was correct or not, you would do it to see how multiple factors interact. With those multiple factors in mind, you would ask the player what they saw and how that influenced their actions. You’re not trying to ascertain if they noticed the “right” things or not, you’re learning what they’re paying attention to so you can give them feedback relevant to what they noticed instead of about what you noticed.

Remembering that events have multiple causal influences means that focusing on one thing or another isn’t necessarily right or wrong, just different. People can reach different decisions and actions, depending on what they choose to focus on as they gather information. If you think they should have been focused on something else, you can ask them questions like, “if you’ve been focused on x, what would happen if you focused on y instead?” Questions like that help both of you acknowledge multiple inputs.

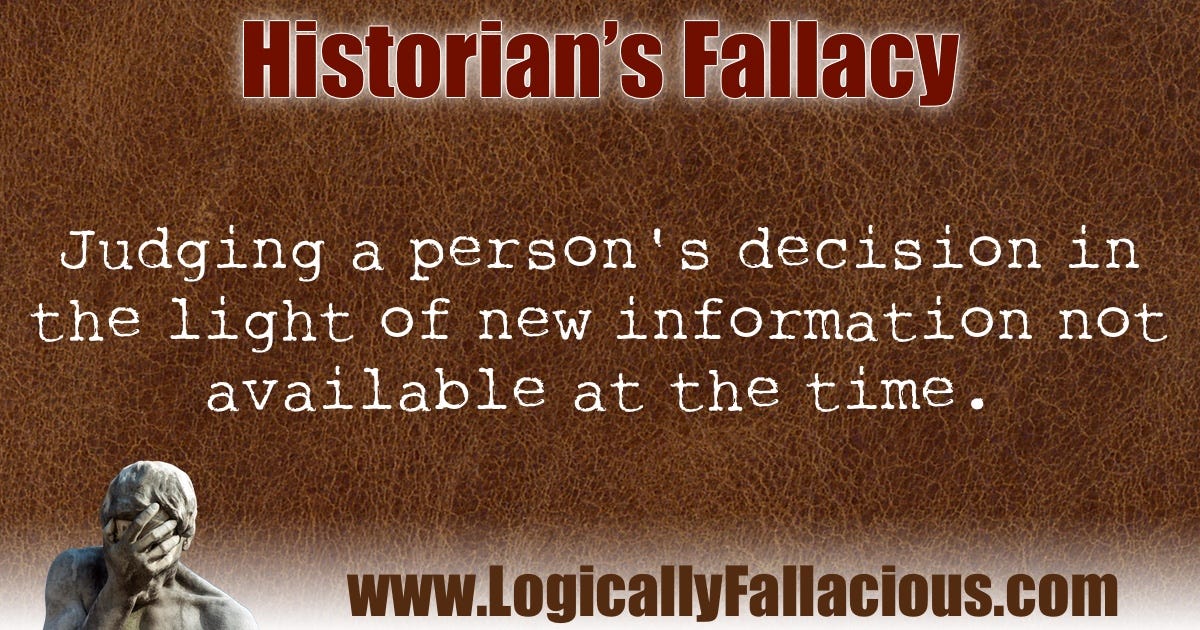

The second trick your brain is constantly pulling on you is called hindsight bias or the historian’s fallacy. Here’s a description of that trick:

I found myself falling victim to this trick as I listened to an episode of Coach Your Brains Out featuring Mike Wall. At the time it was recorded, it was not yet public knowledge that he had joined the staff of the USA Women’s National Volleyball Team but the announcement had been made before the episode was released. As a result, I listened to the podcast with an expectation that Wall would talk about how he would coach that team. But that’s the historian’s fallacy in action because I listened to the conversation using new information that was not available when the conversation was recorded.

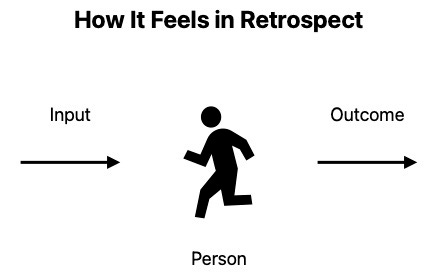

Very often in sports, the new information that becomes available is the outcome of a situation or a decision. At first, it’s really difficult to see how your knowledge of an outcome affects your coaching. What hindsight bias does is take your knowledge of the outcome and make you think that it was the only outcome that was possible. But outcomes are rarely certain, they are usually probabilistic, meaning that there are actually several possible outcomes, each with a certain probability of occurring, even given the same inputs. Hindsight bias is another way of (incorrectly) simplifying “how things happen”.

But, unlike causal reductionism, which affects how you perceive the inputs, hindsight bias affects how you perceive both the inputs and the outcome. When you see one specific outcome, you ignore all the other possible outcomes, no matter how likely they were to happen. Then, your brain quickly constructs a story that explains that one outcome, no matter how rare, by choosing a string of single inputs that conveniently line up to make the outcome you observed practically certain. But that’s not how it actually happens. If you want to be aware of hindsight bias in your coaching, you should think about things happening more like this.

Keeping track of the probabilistic nature of sports is usually thought of as the domain of statisticians and analysts but it’s still your job to keep track of hindsight bias. As a coach, you don’t have to know what the probabilities of different events are. But you should remind yourself of the existence of those possible outcomes because they should affect how you coach. Multiple possible outcomes mean that you or an athlete can make the same decision in the same situation but get different outcomes due to chance, luck, or other inputs out of your control. That means that outcomes aren’t always tightly correlated to your decisions. As Annie Duke wrote in Thinking in Bets, that also means that you should judge the quality of decisions on the process used to make them, rather than judging them based on the quality of the outcomes. You (and the players) can make the best possible decisions but still not have things go your way. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that you and the players have full control over outcomes that you can actually only influence.

An awareness of hindsight bias mostly results in internal changes in your coaching but those changes lead to different ways of giving feedback. When you recognize that a particular event was only probable and not certain, you become less likely to give feedback as if the outcome was always completely under an athlete’s control. You create space for opponents to make good plays or for athletes to just have been exceptionally unfortunate or fortunate in a particular moment. As you become more comfortable with the fact that winning and losing are only loose signals of decision quality, you get better at mentally separating out the role that luck plays in your results from the role that your decision-making plays, and at judging yourself and others based on the latter. (This last sentence is a paraphrasing of Julia Galef from her book, The Scout Mindset.)

The goal of a coach shouldn’t be to eliminate these two tricks of the brain. The goal should be to incorporate knowledge of them into your coaching processes. Admitting they exist and they happen to you isn’t admitting defeat, it’s dealing with the complex reality you coach in and coaching better as a result of that knowledge.

When I first started playing Rec volleyball 40 years ago, our 'captain' was this British fellow whose favourite phrase was 'Ohhh, just unlucky'. At the time, I thought he was just being kind. Turns out, he was onto something. LOL. I preach to my team that all we are doing when we practice is learning to put ourselves into the best position possible to increase the odds of winning the next point. The rest is not for us to say. The future's not ours to see, what will be, will be.

Great article… kind of feel like there’s something about momentum in sports written between the lines here 😉