Doing Extra and Being Extra

And Snakes. Why Did It Have to Be Snakes?

I had a conversation recently with another coach and the topic of private lessons came up. Private lessons are a tough conversation topic because they are simultaneously great and terrible. As with many other things I write about, the context matters. I can’t tell you where on the spectrum lessons you give belong without knowing why you’re doing them and why the athlete you’re working with is doing them.

You’ll notice that I said I want to know why you’re doing them, not that I want to know what you’re doing. Yes, lessons can be great or terrible because of the methods used to conduct them. You might think I want to get into subjects like blocked repetition or representativeness. But that’s not what I want to bring up at all. It’s not that I don’t think such discussions are important, but I think talking about why should come before talking about how.

I think it’s important to recognize why you choose to walk into a lesson, regardless of how you intend to conduct it. The easy answer is you want to help an athlete get better but there’s so much to unpack in that “easy” answer. Implicit in that answer is the belief that the athlete can get better, which is a great attitude to have. But what’s also implicit in that answer is what it takes to get better. Does it just take extra time and training to get better? Often, yes but that’s not universally true for lots of reasons. Maybe the way you choose to work on something isn’t particularly efficient. Maybe the athlete is on a plateau that takes a long time to get off of. But even how long it takes isn’t what I’m getting at.

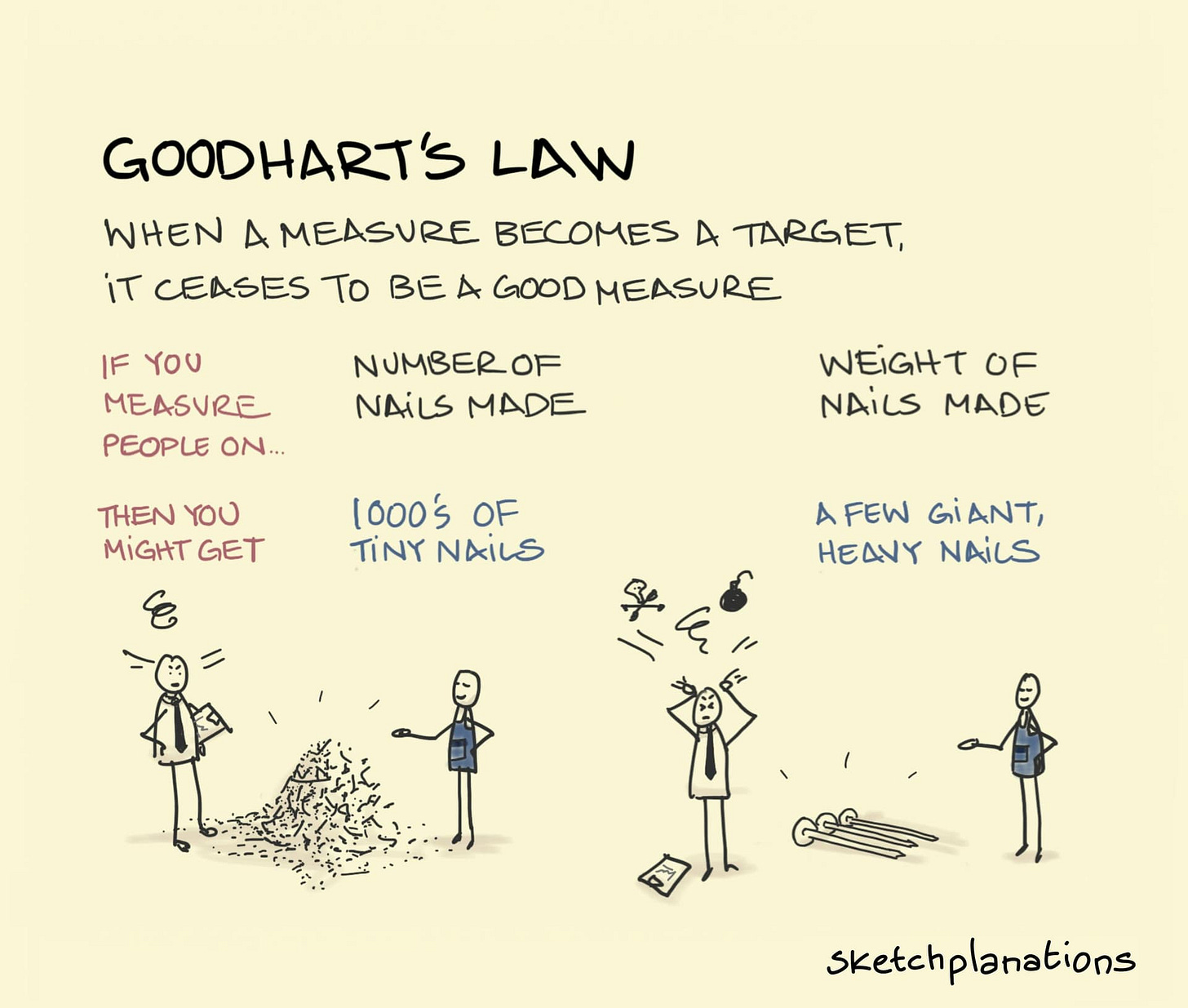

The problem is that coaches and athletes have fallen prey to the cobra effect (or Goodhart’s law or Campbell’s law, or perverse incentives, take your pick of which one makes the most sense to you). The lefthand part of the sketch below sums up what’s happening with lessons really nicely.

The goal of lessons is to get better. If you’re targeting improvement, the best measure is if athletes get better, and by how much. When that is the target, lessons are useful so it can be understandable to equate attending lessons with getting better. The cobra effect applies to lessons because attending lessons became the target instead of getting better. At some point, equating the act of going to lessons with actually getting better resulted in athletes thinking the important thing was attending lessons. So they ask for more and more lessons, thinking that by doing so, they will be considered better automatically. They assume that doing lots and lots of lessons means they’re committed to being great but the problem is they’re making lots and lots of tiny nails instead of making fewer, higher quality nails.

Coaches are complicit in this for a variety of reasons. The biggest issue is you want to reward athletes for doing extra and end up rewarding them for being extra. Being extra, according to Urban Dictionary, is being exaggerated or over the top. It’s making more tiny nails than anyone knows what to do with. Athletes ask for lessons because they think that’s the kind of person they need to be to get ahead. Coaches aren’t clear enough that being extra isn’t an acceptable substitute for being better. You’re not going to start a player because they attended more lessons than another player, you’re going to start them because of their actual skills. That’s what the cobra effect is all about, the players targeting something that doesn’t actually measure the same things coaches are measuring when they make lineup decisions.

So what should you do to remedy the disconnect between what athletes target and what you’re actually measuring? Sometimes, the answer is to do more. When an athlete is less skilled, spending more time in deliberate practice can make big differences. But when everyone is doing more, it’s hard to make any headway by doing even more. To quote Daniel Chambliss1

But at the higher levels of the sport, virtually everyone works hard, and effort per se is not the determining factor that it is among lower level athletes, many of whom do not try very hard. (p. 75 footnote)

When working hard (or being extra) is the norm, Chambliss says it’s time to work differently instead. He explains that highly-rated swimmers swim differently than those with lower ratings (p. 73). To me, working differently means finding different solutions to the same problems the sport presents. It means collaborating with the athlete to learn how many different things they can do instead of how many reps they can get at a single thing. It means putting more tools in the athlete’s toolbox instead of relying on one or two tools.

Another reason to add tools to an athlete’s toolbox is when you recognize that the skill you’re working on is subject to the law of diminishing returns. When the performance curve flattens out, the best choice is to look for another tool to put in the toolbox, another solution to the same problem. Some see private lessons like doing extra credit in school, they are something you do to get ahead or to earn back points you missed. I see lessons more like homework, they are intended to develop new skills and solutions on your own. I want to end lessons by telling athletes to take the new solution we worked on and try it during their regular practices. Take that solution and see if it makes sense when you’re in your normal setting. That’s how you help athletes keep getting better, that’s helping them do extra.

Chambliss, D. F. (1989). The Mundanity of Excellence: An Ethnographic Report on Stratification and Olympic Swimmers. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/202063