Maddie Beal is wonderful blend of learner, teacher, competitor, and coach. She’s not afraid to reflect on, rethink, and change what she does, even in high-achieving, high-expectation environments. She is an assistant coach at Michigan State University.

What are Drills in Depth? - Read here

You may know this drill, I certainly do. And yet my discussion with Maddie is about so much more than just the drill. I encourage you to keep reading, especially if you already know Ball Setter Ball Hitter.

The Drill

Who: Maddie uses this drill regularly with her NCAA Division I women’s volleyball team but she first experienced while playing club volleyball in high school. We also discussed ways to adapt it for different skill/age groups. It likely makes the most sense to use it with teams that have some ability to block although it can certainly be adapted for use with any team that is capable of structured play (pass-set-hit). Depending on how much ball control is desired, a coach may make the first team contact on the offensive side.

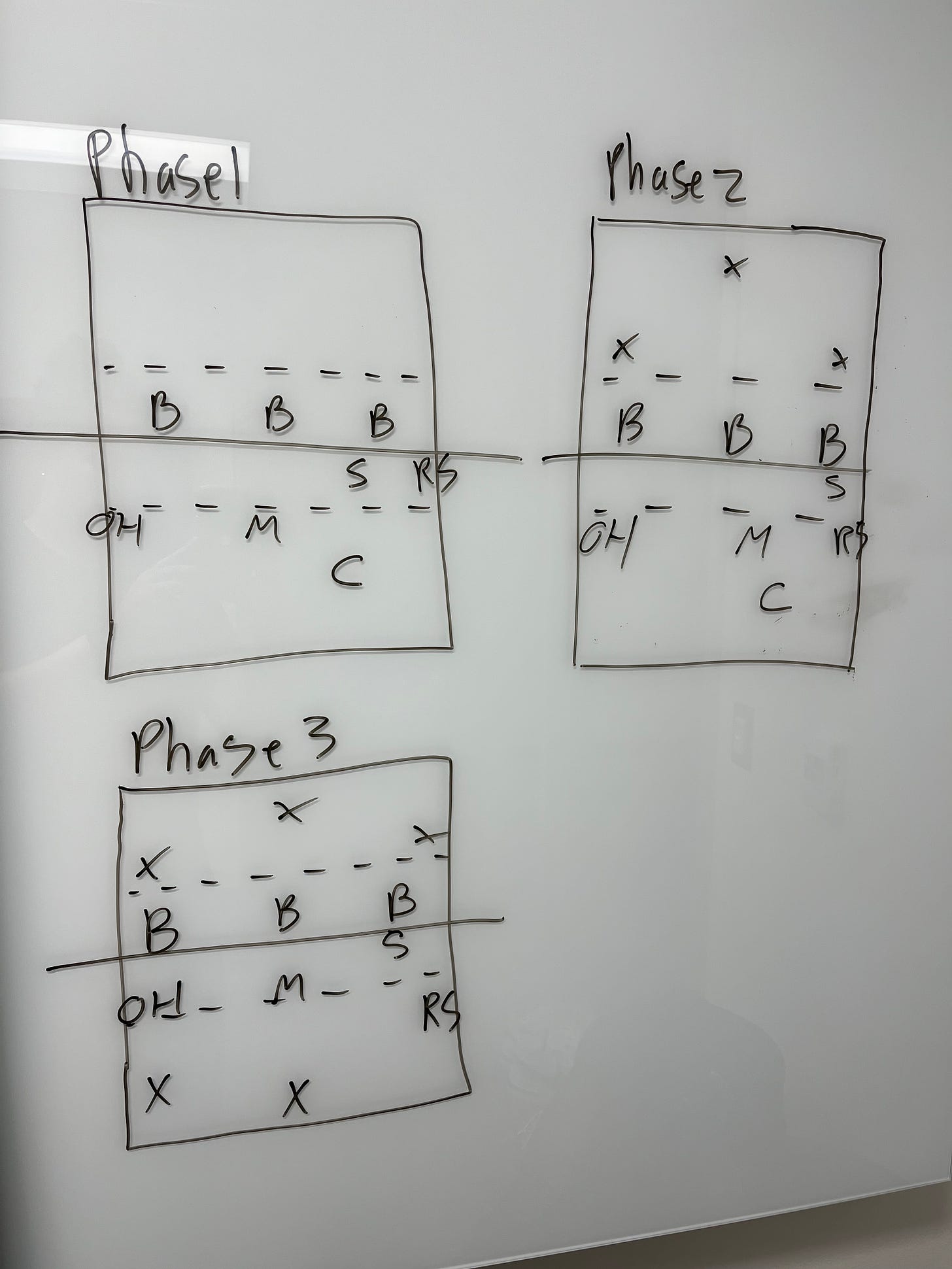

What: Maddie and I discussed three phases of Ball Setter Ball Hitter (BSBH) that make up a gradual progression in drill complexity (see the picture below). In phase 1, there are three blockers on the defending side of the net and three attackers, a setter, and a coach on the attacking side. The ball need not cross the net. In phase 2, three back row defenders are added to the blocking side of the net and the ball still might not cross the net. In phase 3, both sides have a full complement of six players and the ball should cross the net, with rallies being played out. In these rallies, the offense is attempting to score whie the defense is attempting to return the ball. There are possible variations within any phase. It is not necessary to use all phases all the time, coaches can use whichever one(s) might fit their needs in a particular practice session.

When: Maddie finds this drill useful at any time of the season. She remembers this drill being a staple during her collegiate playing career at Minnesota. She can hardly remember a practice when she and her teammates didn’t play some form of BSBH. During those practices, it was typically the first drill of the practice in which all players would be on one court together after starting practice on separate courts working on technique. In general, Maddie sees practices as having a three-part structure, first positional work, then collective learning work, then competitive play. She sees BSBH being used as either more for learning or more for competition, depending on how it is structured. When it is used more for learning, she would use it earlier in a practice session but she would use it later if the intent is for it to be more competitive.

How: In its most elementary phase, play begins with the setter at the net either tossing or hitting a ball to a coach in the back court. The coach passes the ball back for the setter, but not necessarily directly to the setter. Maddie reminded me that BSBH is all about eye work and that’s because the defenders need to verbally identify where the ball is going when the coach passes it. The typical choices for defenders are to classify the pass as off, on, or over. Depending on the defensive system in place, the defenders may respond differently once they determine the pass location. The defenders then call out where the set goes, saying front, middle, or back (there’s no back row attack right now). The attackers approach, jump, catch the ball, and give it back to the setter. All players reset and play begins again. In the second phase, the defending side adds three more players and play flows in the same way as in the first phase. If coaches want to increase complexity and/or make the drill more game-like, they can have attackers play the ball to the defense instead of catching it. Play concludes when the defense plays the ball back over the net and then begins again with another ball from the setter to the coach. In the third phase, there are six players on both offensive and defensive sides of the net. Balls are always given to the offense first, whether they start with the setter (as above) or start with ball over the net to the offense. The defense works to dig each attack and get the ball back to the offensive side while the offense works to score against the defense. Since the defense scores by digging and not by attacking, it doesn’t matter how they get the ball back over the net.

When BSBH is played without the ball crossing the net, there is no score, just repetition, although a coach could certainly find ways to score different actions or behaviors on either side of the net. When the ball isn’t crossing the net, pace of play may be slower and coaches may stop play more frequently to teach. Once teams start playing versions in which the ball crosses the net, the pace picks up and Maddie starts scoring the drill by awarding points to the defense any time they dig a ball or block a ball back to the offensive side. Maddie awards a point to the offense if the defense cannot return the ball legally. When both sides have six players, the offensive side can play any ball the defense sends back over. This means that the defense can score multiple points in a single rally since they score with each dig but the offense can only score a single point per rally.

Maddie will play timed rounds with players rotating through both sides by position. She has found that 2 minutes is her favorite amount of time for a round. If rounds are much longer than that, it becomes physically difficult for defensive players to keep going hard. Each player keeps track of the points their team scores when they’re on the court. As a result of the time limit and the scoring, the pace of the drill is usually fairly high because players want to have as many chances as possible to score points so they want balls put in quickly. While there may be an overall “winner”, it gets cloudy because players may not all play the same number of rounds. Maddie talked about scoring being useful to compare players within position groups, keeping track of which players tend to consistently score more points than others.

The Depth

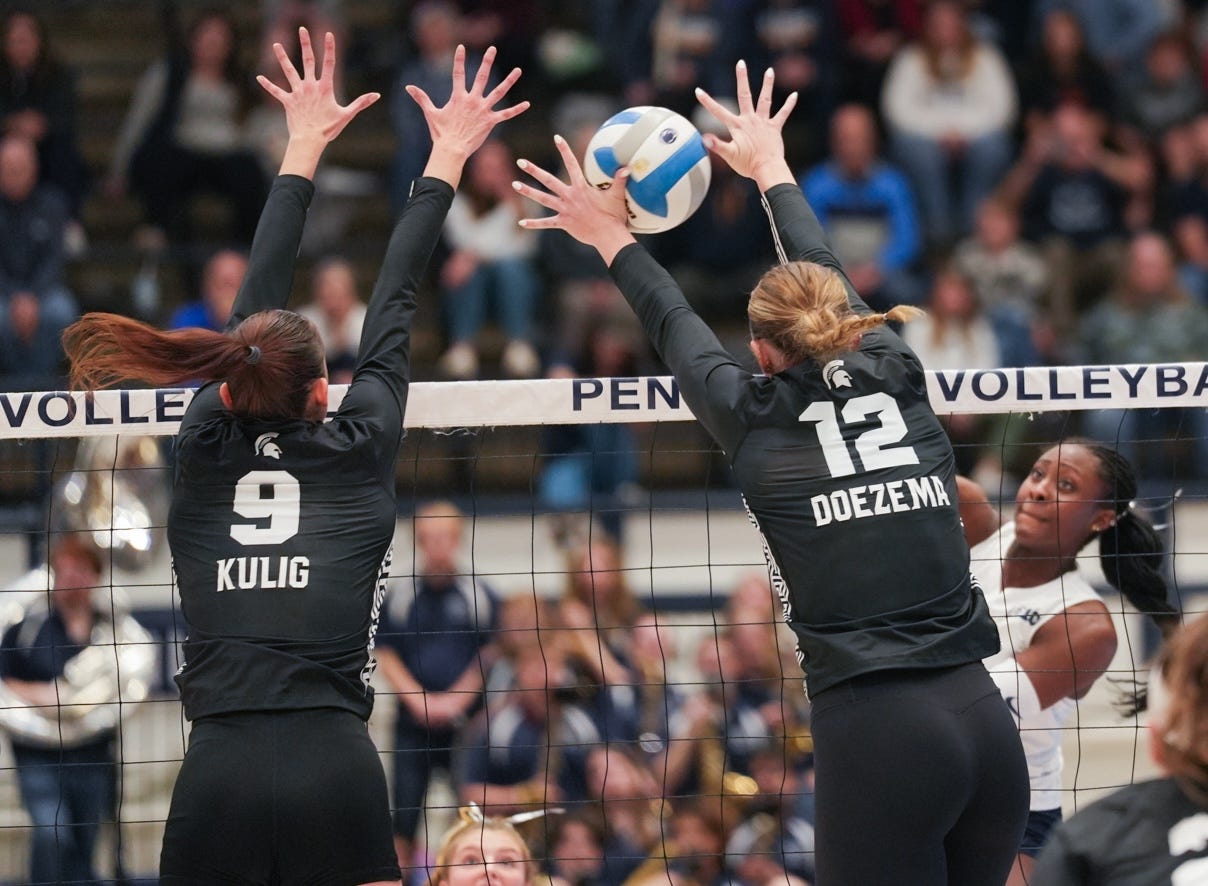

Who: After the 2023 season, Maddie studied the top blocking teams in NCAA women’s volleyball to see what she could learn from watching video. She used several questions to shape how she watched that video and what she would take away from it. Going into the project, she decided to put herself not only in opponent coaches’ shoes, but even thought about what she would coach like if she was on their staff. She compared that to what she had done at MSU in the previous season. Here’s what she was asking herself:

What is their eye work and what are they watching mostly?

Do they do anything differently when blocking an opponent that is in system versus one that is out of system?

What do they look like when blocking 1-on-1? When in a double block?

How does their blocking differ from ours?

What are the cues I think they might be using based off of the video I am seeing?

What would I be teaching to players (techniques and systems) if I was coaching their team?

[I think the last two questions on this list are amazing. She’s not just reverse engineering how an opponent might be teaching and training but she’s also asking herself how she would coach to get the behaviors she’s seeing.]

As a result of the questions she asked in her studies, she came into MSU’s next training block with a much different approach to coaching the blockers. She realized “my coaching needs to be less technical and rigid”. The change was uncomfortable for her at first but she found that, as her coaching became more relaxed, the players were more engaged and athletic. She spent less time talking about specific footwork and more time talking with players about things like if they were beating attackers to the ball. She felt like training was getting better results despite her initial discomfort. Maddie also asks a lot more questions to the players than she used to. She said that she had to learn to ask questions rather than give direct feedback to players. For her, the goal of asking questions is to come to an answer together with them. She wants to help them through their learning process and she has learned that she can do that better if she shifts from defined feedback to asking questions.

What: Ball Setter Ball Hitter focuses on eye work and some coaches interpret that to mean making sure that players are looking at the right things. They may have their players call out where they’re looking to ingrain the eye sequence. But, to Maddie, it isn’t about getting that particular sequence right. (If she’s working with beginners, she might actually have them focus on learning the sequence but that’s not the focus with more experienced players.) In BSBH, she wants to work with players on what they see and what they do, given the situation they observe. Players aren’t scoring points by looking at the right things, they are scoring points by making defensive plays so they need to learn how to respond to what the offense is doing. That’s why she has players identifying what’s happening (on, off, over) rather than where they’re looking (ball, setter, ball, hitter). But that’s just a first layer. “‘What did you see?’ is my favorite question,” she told me. She’s not telling them what they saw, but rather she’s helping them interpret and act on what they saw. Her discussions with players are about helping them find strategies that help them close more blocks and touch more balls by interpreting what they see more efficiently.

When: You can tell when in a practice BSBH is being played by noticing where Maddie is standing. When her team is in a competition-focused phase of the drill, she will watch from the offense’s end line so that she can see “what [the blockers] are looking at and how long it takes them to decide.” Occasionally, she will go to the defense’s end line and focus more on the blockers’ movements. (She is responsible for Michigan State’s blocking, hence her focus on those players.) As mentioned above, the pace of this drill when sides are competing can be quite high so Maddie waits until players are off the court to talk with them about their time in the drill. When they are in a more learning-focused phase, she will stand closer to the net so she can have more frequent conversations with players rather than waiting until they are off the court. By changing where she puts herself, Maddie demonstrates that the same drill is serving different purposes at different times in a practice.

How: As we’ve seen in previous drills (like Rob Graham’s XONTRO and Jon Newman-Gonchar’s 3 Each Way), Ball Setter Ball Hitter offers a lot of opportunities for scoring variations and scouting considerations. Maddie talked about how, during BSBH, the offense can run different attack patterns to simulate those of an upcoming opponent. This gives defenders opportunities to see and respond to what that opponent will likely do while also continuing to build habits within their defensive system and competing against one another. Maddie and I discussed several ways that scoring can be used in BSBH to bring attention to different aspects of defense. For example, if the team is working on defending tips, scoring can be adjusted to reflect that. On the more punitive side, the defense can lose all their points (go back to zero) if they let a tip fall without sufficient effort. Framing it more positively, the defense can earn two points instead of one for successfully digging and returning a tip from the offense.

Where I learned the most in my conversation with Maddie was hearing her talk about discipline. She said that her playing career was and her coaching style is defined by discipline and BSBH gives her a way to coach discipline. I asked her how she defined discipline and she said, “doing what you’re told.” And yet, when she described her evolution as a coach, it became clear that there was a great deal of nuance to what that simple phrase really means to her. Maddie has a strong inner voice that tells her what she needs to do and she developed that inner voice through years of play. Discipline, to her, is doing what you tell yourself to do. When she started coaching, she told players what to do, just as she would tell herself what to do every day and every play. Instead of being their voice and telling them what to do, she’s now helping them develop their own voices by asking them questions. When she talks about helping players through their learning process, I realize that what she’s doing is teaching them discipline by nurturing their inner voices.

Have questions for Maddie? You can ask me here or you can email Maddie directly.