What is confidence? Is it coolly sinking the go-ahead basket as time expires? Is it calling your shot before hitting a home run? No. These actions might be expressions of an athlete’s confidence, but the truth is that confidence is the feeling1 that precedes those actions. And that feeling follows the thought of possibility. Confidence sits between thoughts and actions.

In the post above, I laid out a reactive thought cycle, which consists of “do, feel, think”, as a way of describing how many athletes go through learning and performance. A reactive thought cycle is one in which everything follows action. Actions cause you to feel certain things, and those feelings cause certain thoughts. To oversimplify: you do something well, then feel confident for having done it well, then analyze your action and emotional response, making the connection that feeling good follows doing good. In more academic terms, you learn that competence must precede confidence. Falling into a reactive thought cycle is one way athletes come to think that they have to already be good at something in order to feel confident in their abilities.

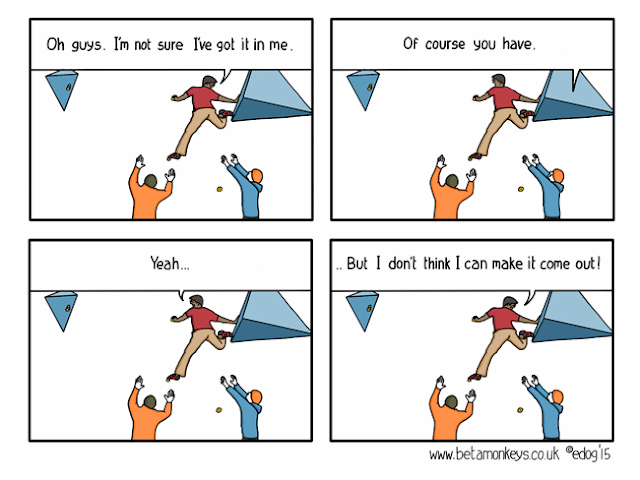

In a reactive thought cycle, confidence bridges between what you did and what you think. As a result, what you think is limited by your confidence and your confidence is limited by your previous actions. This is where many athletes get lost. If they treat confidence as only following competence, they will never feel good about their play unless they are successful. This is one possible source of perfectionism. Perfectionist players may seek perfection because they see it as their only route to feeling good about their play. You can help players break that cycle by teaching them how learning works. First, improvement doesn’t go from nothing to competence in one leap. Second, improvement isn’t steady. (The video below comes from Trevor Ragan’s website, The Learner Lab.) The athlete in the video didn’t dream up the trick and just go out and nail it. He doesn’t always fail in the same ways. Since the video is edited, you can’t tell if the attempts show a clear progression which lead to eventual success. I’m willing to bet that they don’t, which helps explain some of his frustration.

The athlete in the video also shows a much better way to use confidence. To do so, he demonstrates a proactive thought cycle, which consists of “think, feel, do”. This thought cycle is a good way to give yourself more control of your internal environment. In it, confidence is a feeling that acts as a bridge between what you think and what you do. To understand how confidence functions in this thought cycle, I need to introduce one more idea, self-efficacy.

Confidence is an emotional expression of thoughts of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy means thinking that you can do something. That's all. It is a thought that you are capable, regardless of if you’ve actually done the thing or not. If you think you can, that's self-efficacy, which creates fertile emotional ground that can give rise to confidence. So an example in a proactive thought cycle is thinking that you are capable (self-efficacy), which sets you up for feelings of confidence as you visualize yourself performing a skill successfully. These thoughts and feelings put you in the best position to go out and perform, all because you thought and felt that you could. This process doesn't have to begin with any proof, just a thought. This is an idea that lies at the center of Albert Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory, that we come to believe we can do something because we have seen it done by others. According to Bandura, people with high self-efficacy are more likely to see difficult tasks as worth engaging in rather than seeing them as worth avoiding. The skateboarder above appears to be a great example of someone engaged in a difficult task.

It would be easy to just say that the guy had confidence in his abilities and preach the importance of confidence to athletes. But digging into how self-efficacy, confidence, and competence interact will make it easier to teach athletes how to build confidence. The first step is recognizing when you and/or athletes in your care are stuck in a reactive thought cycle, as described above. If you view confidence primarily as a product of competence, then the ways in which you can teach confidence become very limited. A reactive thought cycle begins with action, which means that players start from a position of zero confidence because they are waiting until after they do something to gain confidence. Shifting to a proactive thought cycle opens up more avenues for your coaching. A proactive thought cycle begins with only thoughts and, with the right thoughts, a player can begin learning and exploring with some confidence.

Self-efficacy is a thought of possibility, a thought of I can. In a proactive thought cycle, a player can be invited to start with thoughts of self-efficacy, even if they are trying something completely new to them. You can coach that by showing that player examples of others doing a thing the player hasn’t done yet. To improve the effectiveness of this method, it’s best to find examples of players that look similar to the player you’re coaching2. If you’re somewhere in which the player is surrounded by others similar to them, it’s easy to point out examples. If you’re not in a setting like that, the internet is a great tool for finding video of similar-looking players. Also, you can help a player understand that they might not be great at this new thing for a while but that doesn’t mean that they’ll never be great at it. If they can, so can you. There was a time when they couldn’t, but they worked through it and so can you. That’s coaching self-efficacy.

In a proactive thought cycle, feelings follow thoughts. When a player starts with thoughts of self-efficacy, then feelings of confidence become expressions of trust in those thoughts. You already know a great way of coaching confidence that comes from self-efficacy, “trust the process”. When a player believes they can or will be able to do something new, you can coach them through failures and setbacks by reminding them that the possibility of success still exists. You can keep their focus on learning, progress, and process. Since their confidence isn’t being driven by competence, it’s easier for them to maintain their focus because they are less likely to get caught up in other, often negative, emotions.

So what is confidence? When viewed through the lens of a thought cycles (both proactive and reactive), it’s a feeling. Confidence is a feeling of trust. In a reactive thought cycle, that trust is in previous actions. While this trust is useful when considering something you have already done, it can be inhibiting or even destructive when learning something new. In a proactive thinking cycle, you are trusting yourself in a different way, a way that lends itself to effort, exploration, and even struggle. When your trust is rooted in thoughts of self-efficacy, you are trusting in your ability to change, to try, to overcome setbacks. That kind of confidence is more robust and more positive. That’s the kind of confidence I want to help others build.

The above comic is used with the permission of the excellent rock climbing comic betamonkeys. Please check it out.

Although “feelings” can also refer to physical sensations, I’m focusing on “feelings” as emotions here. In particular, I’m focusing on the emotion of confidence.

There are plenty of studies of observational learning in the academic literature. Here’s one: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Observational-learning-in-motor-skill-acquisition%3A-Scully-Carnegie/8411ea0a4c6d91eb9282d142853a29eddc01baf7