Accountability Through a Different Lens

It’s about being on the same page. And fairness. Sort of.

I once heard a national team-level coach describe his feeling that “accountability” was often just a word used as an excuse to yell at other people when they screwed up. Whenever athletes in their care don’t do what coaches wished they would do, the coaches yell at them in the name of “holding them accountable”. Coaches wish that one group of players on a team would hold others accountable to signal intrinsic motivation. There are always coaches looking for help getting teams to be more accountable. All of these cases overlook what athletes are being held accountable to.

Generally, athletes are held accountable to some team rule or standard but I don’t want to discuss what kinds of rules and standards are proper for different teams. I want to discuss how different orientations can require coaches to approach accountability differently. I also want to discuss how different athletes or different moments can require different kinds of accountability. To understand why reconsidering accountability is important, you need to view it through the lenses of process/outcome and equality/equity orientations.

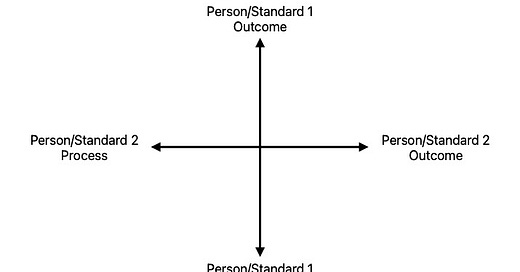

I admit that my choice of terminology doesn’t strictly adhere to what you may find in educational and sport psychology in the area of goal orientation theory but coaches, on the other hand, regularly talk about “process versus outcome”, so the terms should feel familiar. For this discussion, I consider process orientation to be when a goal or person is focused on how something is done regardless of outcome quality, while outcome orientation is when a goal or person is focused on the quality of the outcome regardless of how that outcome is achieved. “Give 100% in practice every day” is a process goal, while “commit fewer than five unforced errors” is an outcome goal. What’s important to consider is how the orientations of two things line up. The two things can be individual people (players or coaches), groups of people, or rules/standards/goals.

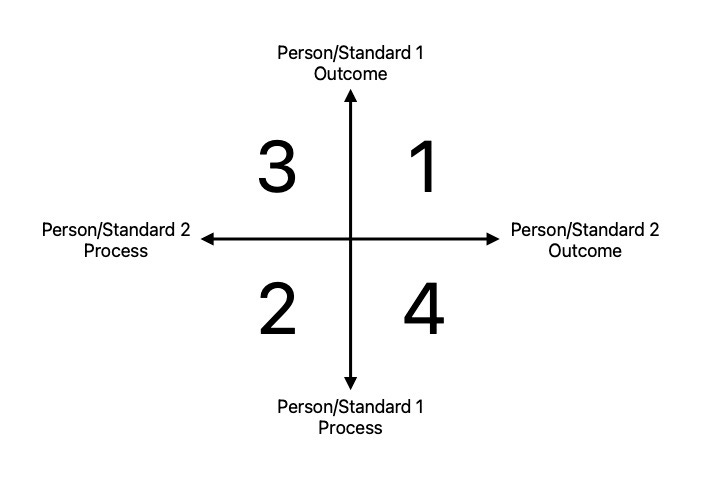

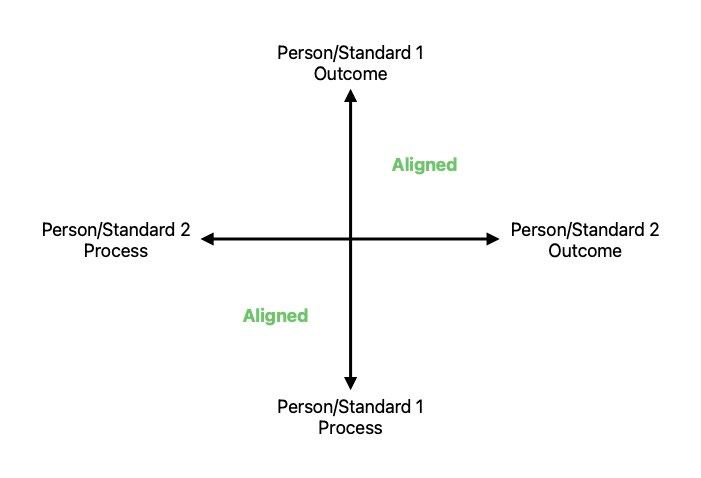

If you assume that each thing’s orientation lies somewhere on a spectrum between outcome and process, then the graph above splits each thing’s orientation into either more towards outcome or more towards process. I’ve numbered the resulting quadrants to make it easier to follow. First, consider quadrants #1 and #2. These two quadrants, while very different in terms of what they might look like, are similar in at least one regard, the orientations of the two things are aligned. Orientations are either both towards outcome or they are both towards process.

I think one issue with how coaches talk about accountability is that they assume that all questions of accountability exist in one of these two quadrants. They think when players aren’t measuring up, the problem is just one of degree, that they are being too much of something or not enough of something, but they also think both coach and players are aligned in what is being measured at that moment. The coach believes the athletes need to be held accountable because they aren’t trying hard enough (process) or they are making too many errors (outcome). Problems of degree are real but they’re not what I’m most interested in right now. I want to get into what happens when you find yourself in quadrants #3 and #4.

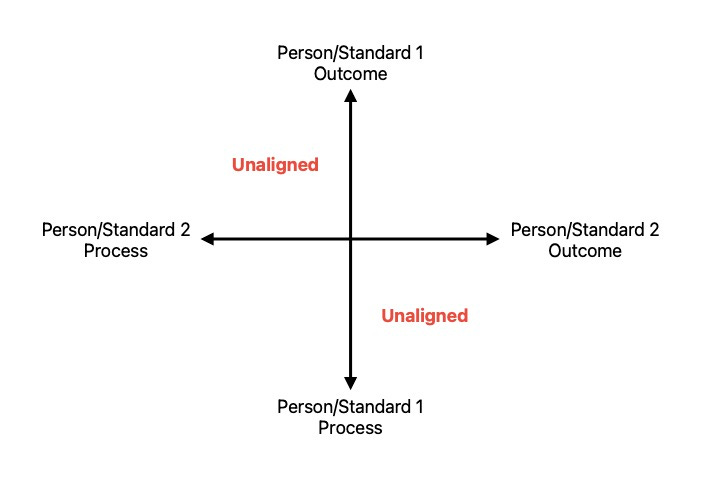

What makes these two quadrants so interesting is problems in these quadrants can present as ones of degree. Why does your most gifted player dog it in practice? What do you do when your hardest-working player can’t crack the starting lineup? It seems like they, too, are not enough of something. The gifted player isn’t focused enough on process while the hardest working one isn’t getting enough of the necessary outcomes. But, when you look more closely, they’re orienting towards the “wrong” end of the spectrum. The gifted player? They’re oriented more towards outcomes. They can get the same outcomes expected of everyone else without breaking a sweat. The great work ethic player? They’re oriented more towards process. They’re doing all the “right” moves but not getting the results you’re demanding. The frustration arises because you’re paying attention to a different end of the spectrum than they are. It gets even more complicated because those two players often exist on the same team and it feels like you’re being inconsistent or unfair unless you’re holding both players accountable to both ends of the spectrum all the time. You expect them to care about the same things you do, as much as you do, all the time. This is what I think that national team coach was getting at, when one person is caring about process while the other is focusing on outcome, so one wants to yell at the other for not being aligned with them.

Managing situations in which people aren’t aligned in their orientations is best handled with clear communication. What are you, the coach, focused on? What do you expect the athletes to be focused on? How have you made your collective orientation clear? How disciplined are you about maintaining that orientation when something outside your focus distracts you? But, even if you and the athletes are all on the same page all the time, that doesn’t solve all the issues.

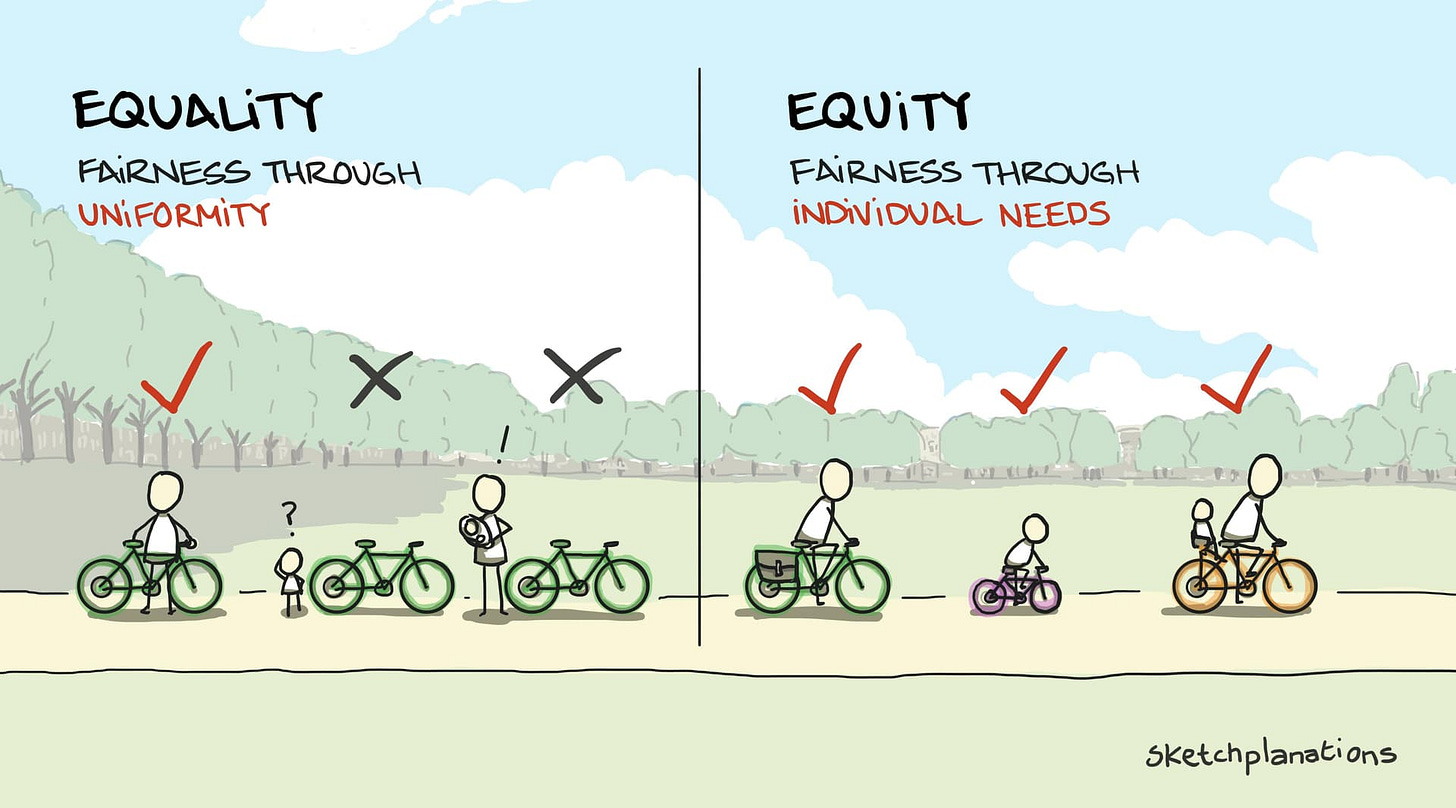

Complication and difficulty in accountability also come from how the concept of fairness is used differently at different times without making the difference in usage clear. Often, people talk about being accountable and fair by applying a principle of equality. I think that you’d often be better served by using a principle of equity to hold athletes accountable. What’s the difference between using equality and using equity?

There are times for equality. If you take your team for ice cream after competition, everyone gets one scoop of ice cream, regardless of how big or small they are or how well or poorly they may have played. That’s fairness through equality. But I think accountability would often be better implemented as fairness through equity. What does that mean? It means accepting that one amount of effort from one player may look very different than the same amount of effort from a different player. It means accepting that, if you want to measure players on outcomes, then you shouldn’t include criteria about how an outcome was (honestly) achieved. But equity isn’t about looking the same.

Viewing accountability as an exercise in equity requires work from you as a coach, particularly with younger athletes. If you and players in your care talk about fairness, you should help them grasp the difference between equality and equity. Your work doesn’t only consist of a quick vocabulary lesson though. You have to train yourself (and them) to see individual differences between players. What do each of them look like when they are giving roughly equal efforts? What do each of them look like when they are competing at their best? What are the outcomes associated with different players showing equal commitments to process? As everyone sees and begins to understand differences between individuals, accountability becomes an exercise in striving together and risking together.

Striving together is about accountability of process. Each person on a team is asked to strive as much as the others, which is fairness through equality. If you judge each person equally then players that make easy plays look more challenging are going to come out ahead and players who make hard plays look easy are going to come out behind. But when each person is asked to recognize and honor what striving looks like in others, that is fairness through equity. The best athlete on your team’s process is going to look different than an average player’s process. The first challenge to equitable accountability of process is to recognize what individual differences look like. The second is to create situations that make those differences more visible. Highlighting physical differences is easy, you make taller players move farther to make the same play. But can you give quicker players less time than average players to make the same plays? Making quicker players move more quickly is an example of equitable accountability of process. It’s about giving them differing opportunities to do the same amount of work.

Risking together is about accountability of outcome. Playing time is often decided by which players create positive outcomes more often, which is fairness through equality. But always judging on equality inevitably leaves some people perennially behind. If some players can never be consistently better than others, those players often question their worth. How can they be seen as having value if they never measure up? Even if they work as hard as they can (becoming very process-oriented), their efforts are perceived as meaningless if everyone is measured equally on outcomes. Gifted players can just be better than others without having to care as much about process. Equitable accountability of outcomes is honoring the risks being taken by each player in search of positive outcomes. Gifted players risk far less to get the same positive outcomes as average players. Risking together means that each player is doing things that give them similar chances of failing. Challenge better players to get balls through smaller spaces than average players. Ask more-skilled offensive players to score against the most skilled defenders. The outcomes might not look very different but, by increasing the chance of failure for the more-skilled player, you are giving all players similar chances at success. Creating equitable amounts of risk for players creates better accountability for all players.

Perhaps the most important aspect of equitable methods of accountability is learning and teaching that this kind of accountability might look a lot different but the goal is to make it feel the same. It’s much easier to judge what everyone can see than it is to judge what each person is feeling. As a result, I think approaching accountability this way requires coaches to teach, embody, and support empathy1 on top of creating more equitable situations. Coaches would say things like, “you know how hard it feels for you to do x? That’s how hard it feels for your teammate to do y.”

One interesting way to measure your efforts at creating equitable accountability is to repurpose the RPE scale you may be familiar with from the strength and conditioning world. Your goal in practice design and execution would be to have player RPEs be grouped together without any outliers for a given session. I don’t think it’s realistic to expect those ratings to all be the same, unless the team is fairly homogenous in skill and work ethic. I think it would be better to use a tool like RPE to help you see where potential accountability issues might arise. Are there players that consistently higher or lower on the scale than their teammates? That might be an indication that there’s work to be done to make things more equitable.

I’m not claiming that approaching accountability equitably will remove difficult conversations around fairness. But I do believe that bringing equity and process/outcome into those conversations will help you make more sense out of challenging situations.

As I was writing this, I thought of the scene below from “Good Will Hunting”. To me, it is a heartbreaking example of just how badly misaligned conversations around accountability can go. (The dialog is NSFW. Will’s potty mouth is on full display in this scene.)