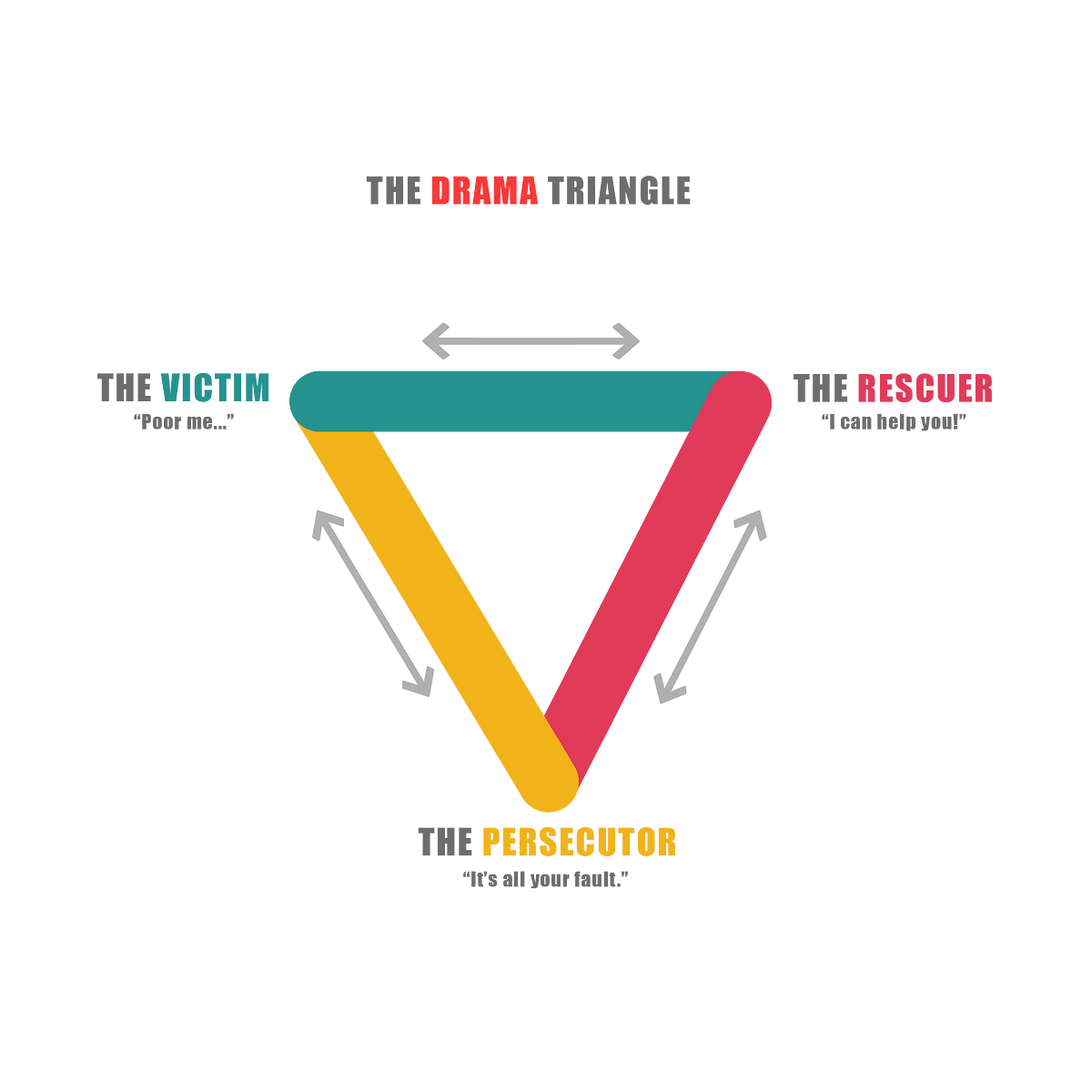

I have a fun puzzle for you. See how many triangles you can find in the image below.

The trick here is there’s no trick here. As far as I know, there’s only one triangle. The problem is there are so many ways to be in one triangle. At least, there are many ways to be in one particular kind of triangle. The particular triangle I’m discussing is the Karpman Drama Triangle. Once you start seeing this one triangle, it’s hard not to see it a lot in coaching.

Even though the roles are fairly clear, the way people experience a drama triangle is far from simple. So when I say there are so many ways to be in one triangle, I mean there are multiple entry points and switching roles is very common and often unconscious. Before getting into the complications, a quick overview of the three roles in the triangle.

Any of the three roles can cause a triangle to form, so the order of the roles doesn’t matter much. Starting at top left of the diagram above, the victim feels like they are stuck in a situation in which they feel helpless despite their best efforts, hence their stance being summarized as “poor me”. Moving to the right, the rescuer feels it is their role to give voice to the victim’s plight since the victim feels powerless, so their stance is summarized as “I can help”. The persecutor is seen as a controlling and critical person who is in charge of a situation, their stance is summarized as “it’s all your fault”.

It’s easy to see how a drama triangle shows up in coaching. Probably the most common is found in club or high school teams, when a player sees themselves as a victim of a demanding coach and the player, by complaining about the situation, invites a parent to come to the rescue. If you’ve ever been a coach in this situation, there are two common things that you’ve done, have a meeting with the player and parent(s), and vent to other coaches about the situation. A common outcome of the meetings is for all parties to become further entrenched in their roles. The coach sees themselves as maintaining their standards and ways of coaching, they just need to explain their actions and decisions so that everyone else better understands what’s happening. Since the player doesn’t feel that anything or anyone is changing, they continue to feel they are the victim, often ignoring the power they actually have to make change because they see any changes as being the result of being told what to do, which reinforces their feelings of helplessness. The parent gets to feel justified in their displeasure towards the coach. The coach feels the player’s and parent’s responses towards them and vents to friends and peers about how futile the whole situation feels, despite their best efforts.

Here’s where a drama triangle starts getting more complicated. The coach has now shifted roles into being the victim. From the coach’s perspective, the parent and player are seen as persecutors because they are making unreasonable demands on the coach. The coach has invited their peers to be rescuers and together, they interpret the future actions of the parent and player as being malicious. When coach, player, and parent are at practice or competition, each person’s thoughts might put them in one role in the triangle while their actions might put them in a different role. It’s very common for each person to hold hidden intentions that allow them to see themselves in a particular role, even though their intentions are meant to actually put them in a different role.

There are lots of reasons to dislike being in a drama triangle but the triangle isn’t about happiness, it’s about letting people feel justified in their unhappiness. All three people have some psychological needs filled by playing their roles, even as those roles change from moment to moment so they rarely see a reason or a way to change.

What I find so difficult and frustrating about drama triangles is they aren’t about change or improvement. Drama triangles exist to give everyone satisfaction in their roles without anyone having to acknowledge the dysfunction of the entire situation. So what’s a coach to do? Break the triangle.

You don’t have to accept the role you’re expected to play. I don’t mean you can just pretend that you aren’t being seen as a persecutor by players and parents or that you can say “I’m not persecuting anyone”. Instead, you can bring everyone stuck in the triangle together and, instead of working against one another, you can work against the triangle. If all of you understand the roles you’re being invited to play, each of you can choose to play roles that don’t fit into a drama triangle.

Often, players feel they are victims when they feel they have no control over what happens to them in their relationships. You can help them break out of that role by working with them on developing their autonomy. To do that, they need to feel like you are working together with them on common goals instead of feeling like you are working on or through them to achieve goals that were assigned to them. This breaks them out of a victim’s feelings of helplessness.

Parents acting as rescuers can frequently increase a victim’s feelings of helplessness when they act instead of the victim. I have seen many teams in which their rules specify that players must bring concerns to the coach before a parent meeting can take place. Such rules are meant to force players out of helplessness but the rules often don’t help as intended because they put the requirement for action on the least powerful party in the relationship. To make those rules function as intended, I believe coaches need to be more proactive in addressing potential concerns rather than being passive and expecting the people with the least experience in uncomfortable conversations to suddenly figure out how to advocate for themselves. By inviting players to discuss how they’re feeling about what’s happening to them, you communicate to them that you are interested in what’s happening to them. If you can keep your discussions with them going, you remove the need for parents to feel that they need to step in and rescue the player.

If you want to transform another person’s life, you have to really transform your relationship with them…We only exist in relation to other people…And so if you want to transform an individual person, in some sense, you have to transform yourself as well.

- Nafees Hamid

I used the quotation above previously when I discussed changing relationships. To break players and parents out of their roles, you have to break yourself out of your role. To break yourself out of your role, you have to change your relationships to others in your triangle. A few terms used to characterize the persecutor are rigid, superior, and controlling. If you want to break out of the persecutor role, don’t be those things. In modern coaching, you might think of being more of a player’s coach. To be clear, you can be a player’s coach without being soft or inferior or abdicating responsibility. Rather than being rigid or soft, be flexible. There are plenty of different ways to achieve similar goals so be willing to negotiate with others about which goals are worth achieving how to achieve those goals. Rather than being superior or inferior, be approachable. I think of this as adopting the old teaching cliché of being the guide on the side rather than the sage on the stage. Look for opportunities to be an advisor instead of always being the director. Rather than abdicating or controlling, model and encourage personal responsibility. The tricky part of this is each person must have meaningful things for which they are accountable. And you need to hold yourself accountable for how well you challenge and support athletes in your care. Luckily, I have some ideas about accountability.

Accountability Through a Different Lens

I once heard a national team-level coach describe his feeling that “accountability” was often just a word used as an excuse to yell at other people when they screwed up. Whenever athletes in their care don’t do what coaches wished they would do, the coaches yell at them in the name of “holding them accountable”. Coaches wish that one group of players on…

Once you start seeing drama triangles in coaching, you start seeing how common they can be and how much they can get in the way of team and individual goals. Ultimately, breaking out of drama triangles takes conscientious work on your part. But, if you ask me, that work is far more rewarding than the work involved in maintaining the triangles. I believe the work is more rewarding because it is focused on growth and improvement. The work challenges you to be a better version of your coaching self while also creating opportunities for real growth in the players in your care.